Problemas Tradicionalistas

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Misa de diálogo - CXIII

Se requiere mayor santidad del clero

Como resultado de la nueva teología del Vaticano II, la comprensión tradicional del sacerdocio como una vocación sobrenatural que requiere un grado de santidad superior al de los fieles ordinarios ha disminuido, o ha desaparecido o se ha relativizado.

El Concilio solo menciona la llamada específica a la santidad del sacerdote ordenado en el contexto de todos los bautizados, religiosos o laicos, que tienen la obligación general de luchar por la santidad en sus vidas. Pero se abstiene cuidadosamente de decir si esta vocación “especial” constituye una forma de santidad superior a la requerida de cualquier otro estado de vida en la Iglesia.

La discrepancia entre el Vaticano II y la enseñanza tradicional se describe claramente en la Carta encíclica a los sacerdotes católicos de Pío XI. Citando a Santo Tomás de Aquino, el Papa afirmó:

La discrepancia entre el Vaticano II y la enseñanza tradicional se describe claramente en la Carta encíclica a los sacerdotes católicos de Pío XI. Citando a Santo Tomás de Aquino, el Papa afirmó:

“Para cumplir los deberes del Orden Sagrado no basta el bien común; pero se requiere una bondad excelente; para que los que reciben Órdenes y por lo tanto sean superiores en rango al pueblo, sean también superiores en santidad.” (1)

Santo Tomás de Aquino nos dice también que un hombre que está destinado al ministerio más augusto de servir a Cristo mismo en el altar requiere una santidad interior mayor que la que se requiere incluso para el estado religioso no ordenado. (2)

Tomás de Kempis dijo que, como el sacerdote está "consagrado para celebrar la Misa", está "atado a una disciplina más estricta y mantenido en una santidad más perfecta". (3) Este requisito, dicho sea de paso, se aplica en diversos grados a los clérigos de las Órdenes Menores y al Subdiaconado, porque participan de las gracias necesarias para su camino hacia el sacerdocio.

Por eso, el Código de Derecho Canónico de 1917 declaraba que “los clérigos deben llevar una vida, tanto interior como exterior, más santa que los laicos, y serles un ejemplo sobresaliendo en virtud y buenas obras”. (4)

La cuestión, debe enfatizarse, no es y nunca ha sido si un clérigo individual alcanza mayor santidad que un laico individual, sino lo que la Iglesia nos ha enseñado sobre la naturaleza del estado clerical y su relación con la Eucaristía.

Inversión de significados, valores y actitudes

Después del Concilio Vaticano II, la “santidad superior” del clero se convirtió repentinamente en un tema tabú, arrojado a las tinieblas exteriores, para ser reemplazado por el eslogan “la llamada universal a la santidad” que se encuentra en Lumen gentium.

Pronto se vería que esto no transmitía el significado tradicional de que todos los bautizados, sin importar su estatus en la Iglesia, deberían luchar por la perfección en la vida cristiana. En cambio, se usó en el sentido de "igualdad de santidad para todos" y se ponderó en contra de aquellos que tenían más que perder por una degradación de su estatus superior, es decir, clérigos en órdenes menores y mayores.

Invirtiendo la enseñanza recibida y aceptada de la Iglesia sobre la necesidad de una mayor santidad para los ordenados, el Papa Juan Pablo II declaró: “En verdad, el sacerdocio ministerial no significa por sí mismo un mayor grado de santidad con respecto al sacerdocio común de los fieles. ” (5)

Esta declaración es una contradicción explícita del testimonio común de la Iglesia hasta el Concilio Vaticano II que colocaba a todas las órdenes clericales por encima del estado laico en términos de la santidad de su oficio en la medida en que se acercaban más al sacerdocio de Cristo. Viniendo del Papa, es moralmente indefendible porque, al igualar los estados clerical y laico, degradó indirectamente el ministerio petrino por el cual se le dio el título de Su Santidad en reconocimiento a la santidad preeminente de su oficio.

La idea, sin embargo, de desinflar el estatus superior del sacerdocio no se originó con Juan Pablo II a pesar de que intervino con éxito, como veremos más adelante, en el Vaticano II para introducirlo en la Lumen gentium cuando era un obispo joven. Un peligroso precedente ya lo había sentado el fundador del Opus Dei, Mons. Josemaría Escrivá, que escribió en 1945:

La idea, sin embargo, de desinflar el estatus superior del sacerdocio no se originó con Juan Pablo II a pesar de que intervino con éxito, como veremos más adelante, en el Vaticano II para introducirlo en la Lumen gentium cuando era un obispo joven. Un peligroso precedente ya lo había sentado el fundador del Opus Dei, Mons. Josemaría Escrivá, que escribió en 1945:

“Tanto los sacerdotes como los laicos, en razón del único bautismo que han recibido, deben aspirar igualmente a la santidad… la santidad a la que son llamados no es mayor en el sacerdote que en el laico, ya que éste no está llamado a ser de una segundo clase cristiana. La santidad, tanto en el sacerdote como en el laico, no es otra cosa que la perfección de la vida cristiana”. (6)

La implicación aquí es que la ordenación no eleva al sacerdote a un rango espiritual o grado de santidad superior al de los laicos. Pero esto es diametralmente opuesto a la enseñanza establecida de la Iglesia, y choca frontalmente con lo que Pío XI había afirmado solo unos años antes en su citada Encíclica sobre el Sacerdocio Católico.

Así que la visión de Mons. Escrivá sobre la Iglesia y su organización no es coherente con la concepción católica del sacerdocio. Fue una construcción intelectual típica de los innovadores teológicos progresistas del siglo XX que querían promover la “participación activa” de los laicos como el principio supremo.

Su insinuación de que el laico era tratado como un “cristiano de segunda clase” en la Iglesia era parte de su proceso de pensamiento revolucionario y está imbuido de un tono neomarxista. Sugiere que las masas no ordenadas son víctimas de una discriminación injusta por parte de los ordenados (los pocos privilegiados). Era una forma disfrazada de “teología de la liberación” que bien podría denominarse “opción preferencial por los laicos”.

Sin embargo, en un mensaje enviado por el Vaticano en 2013 al Opus Dei elogiando la contribución de su fundador a la teología, el Papa Francisco llamó a Escrivá “un precursor del Vaticano II al enfatizar el llamado universal a la santidad”. (7)

El nuevo lema: 'la llamada universal a la santidad'

La Iglesia siempre ha enfatizado la necesidad de que todos los cristianos, sin excepción, trabajen hacia la perfección espiritual, un imperativo basado en la enseñanza de Nuestro Señor (Mateo 5:48). Pero en manos de innovadores teológicos, este pasaje de la Sagrada Escritura se convirtió en un arma ideológica para mantener la fantasía de que no existe una mayor santidad asociada al sacerdocio.

Obvias consecuencias negativas surgieron de la amplia difusión de esta consigna en un sentido desfavorable para el clero. Si la Ordenación no eleva al sacerdote a un grado de santidad superior al del estado laical, entonces su naturaleza esencial de ministro de lo sagrado queda degradada al nivel de todos los bautizados.

Obvias consecuencias negativas surgieron de la amplia difusión de esta consigna en un sentido desfavorable para el clero. Si la Ordenación no eleva al sacerdote a un grado de santidad superior al del estado laical, entonces su naturaleza esencial de ministro de lo sagrado queda degradada al nivel de todos los bautizados.

En otras palabras, el “llamado universal a la santidad” era un eslogan con el potencial de disminuir la reverencia debida al sacerdote al convertir su nivel superior de santidad en una masa homogénea de santidad para todos, permitiendo así que lo particular se sumergiera en la santidad. colectivo y, eventualmente, perdido de vista.

A partir de ahí, solo hubo un paso corto hasta la promoción del Vaticano II de la "participación activa" de los laicos y la revolución litúrgica y eclesiástica de la era posterior al Vaticano II. La intención de los progresistas era que, al menos a nivel empírico, el sacerdocio ministerial no debía distinguirse más del sacerdocio común de los fieles. Como resultado, todo lo que se tenía por sagrado en el sacerdocio ha sido rebajado a un nivel común y profano, para adaptarlo al espíritu mundano de los tiempos.

Lo que alguna vez se creyó sobre este tema por los católicos de siglos anteriores, que una mayor santidad conviene al estado clerical que al laico, se ha oscurecido y eclipsado por las nuevas enseñanzas del Vaticano II. Y, en consecuencia, se censura cualquier intento de reiterar la doctrina tradicional, ya que ahora estaría en desacuerdo con la mentalidad oficial, políticamente correcta, de “igualdad de santidad” para todos.

Continuará...

El Concilio solo menciona la llamada específica a la santidad del sacerdote ordenado en el contexto de todos los bautizados, religiosos o laicos, que tienen la obligación general de luchar por la santidad en sus vidas. Pero se abstiene cuidadosamente de decir si esta vocación “especial” constituye una forma de santidad superior a la requerida de cualquier otro estado de vida en la Iglesia.

La enseñanza papal tradicional de Pío XI

llamó al sacerdote a una mayor santidad

“Para cumplir los deberes del Orden Sagrado no basta el bien común; pero se requiere una bondad excelente; para que los que reciben Órdenes y por lo tanto sean superiores en rango al pueblo, sean también superiores en santidad.” (1)

Santo Tomás de Aquino nos dice también que un hombre que está destinado al ministerio más augusto de servir a Cristo mismo en el altar requiere una santidad interior mayor que la que se requiere incluso para el estado religioso no ordenado. (2)

Tomás de Kempis dijo que, como el sacerdote está "consagrado para celebrar la Misa", está "atado a una disciplina más estricta y mantenido en una santidad más perfecta". (3) Este requisito, dicho sea de paso, se aplica en diversos grados a los clérigos de las Órdenes Menores y al Subdiaconado, porque participan de las gracias necesarias para su camino hacia el sacerdocio.

Por eso, el Código de Derecho Canónico de 1917 declaraba que “los clérigos deben llevar una vida, tanto interior como exterior, más santa que los laicos, y serles un ejemplo sobresaliendo en virtud y buenas obras”. (4)

La cuestión, debe enfatizarse, no es y nunca ha sido si un clérigo individual alcanza mayor santidad que un laico individual, sino lo que la Iglesia nos ha enseñado sobre la naturaleza del estado clerical y su relación con la Eucaristía.

Inversión de significados, valores y actitudes

Después del Concilio Vaticano II, la “santidad superior” del clero se convirtió repentinamente en un tema tabú, arrojado a las tinieblas exteriores, para ser reemplazado por el eslogan “la llamada universal a la santidad” que se encuentra en Lumen gentium.

Pronto se vería que esto no transmitía el significado tradicional de que todos los bautizados, sin importar su estatus en la Iglesia, deberían luchar por la perfección en la vida cristiana. En cambio, se usó en el sentido de "igualdad de santidad para todos" y se ponderó en contra de aquellos que tenían más que perder por una degradación de su estatus superior, es decir, clérigos en órdenes menores y mayores.

Invirtiendo la enseñanza recibida y aceptada de la Iglesia sobre la necesidad de una mayor santidad para los ordenados, el Papa Juan Pablo II declaró: “En verdad, el sacerdocio ministerial no significa por sí mismo un mayor grado de santidad con respecto al sacerdocio común de los fieles. ” (5)

Esta declaración es una contradicción explícita del testimonio común de la Iglesia hasta el Concilio Vaticano II que colocaba a todas las órdenes clericales por encima del estado laico en términos de la santidad de su oficio en la medida en que se acercaban más al sacerdocio de Cristo. Viniendo del Papa, es moralmente indefendible porque, al igualar los estados clerical y laico, degradó indirectamente el ministerio petrino por el cual se le dio el título de Su Santidad en reconocimiento a la santidad preeminente de su oficio.

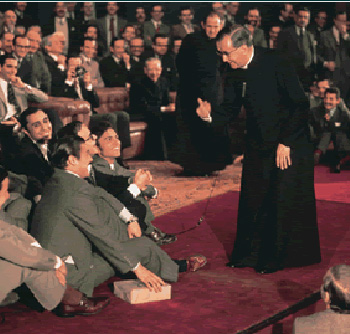

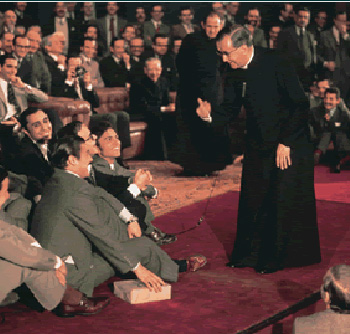

Monseñor Escrivá enseñando a los laicos que tienen vocaciones iguales, abajo, con su buen amigo protector Pablo VI

“Tanto los sacerdotes como los laicos, en razón del único bautismo que han recibido, deben aspirar igualmente a la santidad… la santidad a la que son llamados no es mayor en el sacerdote que en el laico, ya que éste no está llamado a ser de una segundo clase cristiana. La santidad, tanto en el sacerdote como en el laico, no es otra cosa que la perfección de la vida cristiana”. (6)

La implicación aquí es que la ordenación no eleva al sacerdote a un rango espiritual o grado de santidad superior al de los laicos. Pero esto es diametralmente opuesto a la enseñanza establecida de la Iglesia, y choca frontalmente con lo que Pío XI había afirmado solo unos años antes en su citada Encíclica sobre el Sacerdocio Católico.

Así que la visión de Mons. Escrivá sobre la Iglesia y su organización no es coherente con la concepción católica del sacerdocio. Fue una construcción intelectual típica de los innovadores teológicos progresistas del siglo XX que querían promover la “participación activa” de los laicos como el principio supremo.

Su insinuación de que el laico era tratado como un “cristiano de segunda clase” en la Iglesia era parte de su proceso de pensamiento revolucionario y está imbuido de un tono neomarxista. Sugiere que las masas no ordenadas son víctimas de una discriminación injusta por parte de los ordenados (los pocos privilegiados). Era una forma disfrazada de “teología de la liberación” que bien podría denominarse “opción preferencial por los laicos”.

Sin embargo, en un mensaje enviado por el Vaticano en 2013 al Opus Dei elogiando la contribución de su fundador a la teología, el Papa Francisco llamó a Escrivá “un precursor del Vaticano II al enfatizar el llamado universal a la santidad”. (7)

El nuevo lema: 'la llamada universal a la santidad'

La Iglesia siempre ha enfatizado la necesidad de que todos los cristianos, sin excepción, trabajen hacia la perfección espiritual, un imperativo basado en la enseñanza de Nuestro Señor (Mateo 5:48). Pero en manos de innovadores teológicos, este pasaje de la Sagrada Escritura se convirtió en un arma ideológica para mantener la fantasía de que no existe una mayor santidad asociada al sacerdocio.

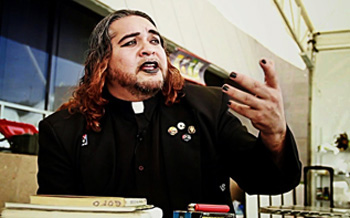

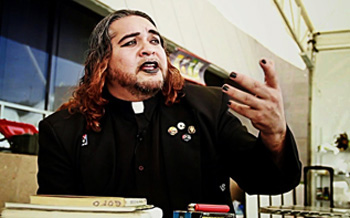

Los sacerdotes ahora se consideran iguales a los laicos; arriba, sacerdotes paulistas en unas vacaciones en bote; abajo, cura del rock popular mexicano 'El Gofo'

En otras palabras, el “llamado universal a la santidad” era un eslogan con el potencial de disminuir la reverencia debida al sacerdote al convertir su nivel superior de santidad en una masa homogénea de santidad para todos, permitiendo así que lo particular se sumergiera en la santidad. colectivo y, eventualmente, perdido de vista.

A partir de ahí, solo hubo un paso corto hasta la promoción del Vaticano II de la "participación activa" de los laicos y la revolución litúrgica y eclesiástica de la era posterior al Vaticano II. La intención de los progresistas era que, al menos a nivel empírico, el sacerdocio ministerial no debía distinguirse más del sacerdocio común de los fieles. Como resultado, todo lo que se tenía por sagrado en el sacerdocio ha sido rebajado a un nivel común y profano, para adaptarlo al espíritu mundano de los tiempos.

Lo que alguna vez se creyó sobre este tema por los católicos de siglos anteriores, que una mayor santidad conviene al estado clerical que al laico, se ha oscurecido y eclipsado por las nuevas enseñanzas del Vaticano II. Y, en consecuencia, se censura cualquier intento de reiterar la doctrina tradicional, ya que ahora estaría en desacuerdo con la mentalidad oficial, políticamente correcta, de “igualdad de santidad” para todos.

Continuará...

- Pius XI, Ad Catholici Sacerdotii, 1935, § 35.

- Summa Theologiae, II,II, q. 184.

- The Imitation of Christ, chap. 5.

- Canon § 124.

- John Paul II, Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Pastores dabo vobis, 1992, § 17.

- Josemaría Escrivá, In Love with the Church, Sceptre Publishers, 1917.

- These words are translated from a telegram sent in Italian from the Secretary of State, Archbishop Pietro Parolin, to the Prelate of Opus Dei (23 November 2013) on the occasion of an International Symposium on the founder’s theological thought.

Publicado el 10 de marzo de 2022

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |