Asuntos Tradicionalistas

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Misa de Diálogo - CXIX

“Clericalismo”: una palabra mal utilizada por los progresistas

Si alguien se pregunta por qué nunca hay buenos "clericalistas", la razón es que los progresistas han dado mala fama a los sacerdotes anteriores al Vaticano II por adherirse a la enseñanza tradicional de la Iglesia, y luego la usaron como un garrote con el que vencerlos.

La fidelidad a la Tradición, por supuesto, no habría sido un problema si no hubiera sido por la nueva enseñanza revolucionaria del Vaticano II que empoderó enormemente a los laicos frente al clero. Cualquiera que no aceptara que el clero y los laicos son socios iguales en la tarea de la Nueva Evangelización y Misión de la Iglesia estaría ipso facto acusado de “clericalismo”.

Pero, ¿qué significaba exactamente este término peyorativo y a quién se aplicaba? Buscaríamos en vano una definición precisa, pero tenemos una regla general aproximada en la siguiente lista de acusaciones.

Manifestaciones del 'clericalismo'

Los progresistas acusan a un sacerdote de ser “clericalista” cuando hace algo de lo siguiente:

La principal reprimenda dirigida al clero tradicional fue que, al participar de una manera más cercana con la Jerarquía, tenían una posición superior al resto de los fieles en la Iglesia. Cualquiera que se niegue a adoptar la noción (esencialmente protestante) de igualdad de estatus entre el clero y los laicos está manchado con el pincel del “clericalismo”. Esta es precisamente la posición del sacerdote del Opus Dei, Mons. Cormac Burke: “La mentalidad clerical considera al clero como superior, con un estatus superior en la vida de la Iglesia; y los laicos como inferiores, en una posición subordinada.” (1)

Estas palabras resumen la actitud revolucionaria que impregna la Nueva Evangelización soñada por el Vaticano II. Están en abierta rebelión tanto contra la Ley Natural como contra la institución de Dios para toda sociedad, incluida la Iglesia, que necesariamente comprende a los altos y los bajos, los superiores y sus súbditos, los dominantes y los subordinados, los que gobiernan y los que mandan, así como los que obedecen.

Estas palabras resumen la actitud revolucionaria que impregna la Nueva Evangelización soñada por el Vaticano II. Están en abierta rebelión tanto contra la Ley Natural como contra la institución de Dios para toda sociedad, incluida la Iglesia, que necesariamente comprende a los altos y los bajos, los superiores y sus súbditos, los dominantes y los subordinados, los que gobiernan y los que mandan, así como los que obedecen.

Este es el sistema de dos niveles descrito por el Papa Pío X en el que sólo la Jerarquía tiene el derecho y la autoridad para gobernar, y en el que los laicos tienen el deber de “dejarse conducir, y como un rebaño dócil, seguir la pastores”. (2) El Papa cita a San Cipriano en el sentido de que los primeros cristianos entendieron que este arreglo superior-inferior se basaba en la Ley Divina.

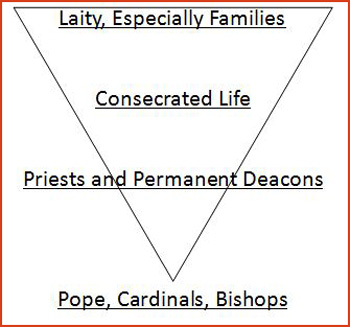

Pero, ¿qué pasa si los pastores quieren revolucionar la Constitución, “invertir el triángulo”, cambiar la Iglesia de una monarquía a una democracia, como exigen los progresistas del Vaticano II, e incluir la los laicos en el gobierno de la Iglesia? ¿Deberían los fieles seguirlos como un rebaño dócil para contravenir la Ley Divina?

Ciertamente, esta no era la intención del Papa Pío X, ya que violaría la ley de no contradicción. Más bien, es en las declaraciones de los obispos progresistas en el Vaticano II, según consta en las Acta Synodalia, donde encontramos amplia confirmación de que el desprecio por la Ley Divina se manifestó claramente entre un número significativo de prelados influyentes y sus expertos asesores que querían subvertir la Constitución de la Iglesia.

Los documentos del Concilio resultantes, que estaban contaminados con esta tendencia subversiva, tuvieron el efecto de llevar a los fieles a una batalla continua y profundamente divisiva entre la tradición católica y las fuerzas rivales del progresismo en la Iglesia.

Lecciones de la historia

Podemos ver la misma Teoría del Conflicto funcionando en la historia de todos los levantamientos políticos desde el destierro del estadista, Aristides en el siglo V a.C., líder del partido aristocrático en Atenas, hasta todas las revoluciones de inspiración marxista de los tiempos modernos, que buscaban destruir lo que consideraban una sociedad intolerablemente desigual.

El destino de Aristides, (conocido por todos como "Aristides el Justo"), quien fue desterrado de Atenas c. 482 a.C. simplemente por ser considerado “más justo” que otros, comparte un punto importante de similitud con la animosidad posterior al Vaticano II hacia el sistema desigual de dos niveles de la Iglesia. Según el historiador griego Plutarco, Arístides sufrió el exilio a manos de los ciudadanos atenienses debido a su “desprecio envidioso por su reputación” y porque estaban “enfadados con aquellos que se elevaban sobre la multitud en nombre y reputación”.

Así que “en un espíritu de odio celoso se reunieron en la ciudad ciudadanos de todo el país y condenaron al ostracismo a Aristides” después de manchar su buena reputación con acusaciones de “prestigio y poder opresores”. (3)

Así que “en un espíritu de odio celoso se reunieron en la ciudad ciudadanos de todo el país y condenaron al ostracismo a Aristides” después de manchar su buena reputación con acusaciones de “prestigio y poder opresores”. (3)

El “ostracismo” era una antigua práctica griega utilizada por los ciudadanos atenienses que ejercían sus derechos democráticos, lo que les permitía desterrar a cualquier ciudadano destacado de la ciudad durante 10 años. El nombre deriva del ostrakon (plural ostraka), un fragmento de cerámica en el que los atenienses grababan el nombre de la persona que querían exiliar, como una forma de emitir votos.

Plutarco relata un incidente divertido que sucedió durante la votación; su relevancia para las sociedades modernas se puede comprender fácilmente porque arroja luz sobre las fuentes de la naturaleza humana que provocan sentimientos de envidia hacia las personas de mayor virtud o posición superior:

“Ahora bien, en el momento del que estaba hablando, mientras los votantes estaban inscribiendo su ostraka, se dice que un tipo iletrado y completamente grosero entregó su ostrakon a Arístides, a quien lo tomó por uno de la multitud común y le pidió que escribiera Arístides en él. Asombrado, le preguntó al hombre qué mal le había hecho Arístides. 'Ninguno en absoluto', fue la respuesta, 'Ni siquiera conozco a Arístides, pero estoy cansado de escuchar que en todas partes lo llamen 'El Justo' "(4)

Hay aquí un paralelismo evidente con el destino de los sacerdotes hoy, que son condenados como “clericalistas” simplemente por ser clérigos y, por lo tanto, de un estatus superior al de sus subordinados, los laicos. Al igual que con el asunto Arístides, el mismo patrón de animosidad se produjo durante la reforma de la Constitución del Vaticano II cuando los progresistas votaron a favor del ostracismo de la Tradición.

Hubo la misma negativa a reconocer la eminencia, como en "No eres más alto que el resto de nosotros" (lo que resultó en la difuminación de la distinción entre el sacerdocio y los laicos); las mismas acusaciones de opresión bajo los poderes gobernantes (Aristides fue acusado del crimen supremo en una democracia: querer convertirse en rey); las mismas técnicas de agitación para poner al pueblo en contra de sus líderes (Aristides fue calumniado por su rival político, Temístocles, quien contó con el apoyo de las clases bajas contra la nobleza ateniense); el mismo enmascaramiento hipócrita de la envidia bajo la bandera de la “justicia” y la “igualdad”; y la misma experiencia de Schadenfreude (5) que en la Iglesia moderna tomó la forma de un cierto deleite en derribar al sacerdote de su pedestal.

A partir de estas consideraciones, no es difícil ver cómo la devaluación del estatus superior del sacerdote inspirada por el Vaticano II fue de la misma época que ese vicio de la naturaleza humana que fue la causa próxima de la Pasión de Nuestro Señor: “Fue por envidia de que los principales sacerdotes lo hubieran entregado.” (Mt 27,18)

En la Summa, Santo Tomás de Aquino trata la envidia como un vicio opuesto a la caridad (6) porque implica la disposición a sentir mala voluntad ante la superioridad percibida de otra persona, lo que lleva a actos destructivos. Durante el Concilio, las acusaciones de “clericalismo” procedían, como más tarde descubrimos, de quienes despreciaban tanto la naturaleza jerárquica de la Iglesia como la diferencia esencial entre el sacerdocio ordenado y el “sacerdocio” de todos los bautizados.

En la Summa, Santo Tomás de Aquino trata la envidia como un vicio opuesto a la caridad (6) porque implica la disposición a sentir mala voluntad ante la superioridad percibida de otra persona, lo que lleva a actos destructivos. Durante el Concilio, las acusaciones de “clericalismo” procedían, como más tarde descubrimos, de quienes despreciaban tanto la naturaleza jerárquica de la Iglesia como la diferencia esencial entre el sacerdocio ordenado y el “sacerdocio” de todos los bautizados.

No es de extrañar, por lo tanto, que tras el Concilio tales actitudes anticlericales se tradujeran en la pérdida, sustracción o entorpecimiento de aquellos bienes que correspondían al clero ordenado: sus Órdenes Menores preliminares, su relación única con la Eucaristía, su función exclusiva en el santuario, la reverencia y deferencia con que eran tratados por los laicos. Todos estos privilegios del clero se convirtieron en objeto de la ira iconoclasta.

Mientras que este tipo de prejuicio anticlerical alguna vez se esperaba solo de herejes e ideólogos seculares opuestos al catolicismo, ahora es dolorosamente obvio que los mismos católicos están abiertamente involucrados en el ataque contra el sacerdocio ordenado.

Continuará...

La fidelidad a la Tradición, por supuesto, no habría sido un problema si no hubiera sido por la nueva enseñanza revolucionaria del Vaticano II que empoderó enormemente a los laicos frente al clero. Cualquiera que no aceptara que el clero y los laicos son socios iguales en la tarea de la Nueva Evangelización y Misión de la Iglesia estaría ipso facto acusado de “clericalismo”.

Pero, ¿qué significaba exactamente este término peyorativo y a quién se aplicaba? Buscaríamos en vano una definición precisa, pero tenemos una regla general aproximada en la siguiente lista de acusaciones.

Manifestaciones del 'clericalismo'

Los progresistas acusan a un sacerdote de ser “clericalista” cuando hace algo de lo siguiente:

- Lleva sotana;

- Se mantiene alejado de las amistades y actividades mundanas;

- Mantiene límites entre él y los laicos;

- Espera ser abordado por su título y apellido;

- Dice misa de espaldas a la gente;

- Usa el latín en la liturgia;

- Sigue las reglas y rúbricas con exactitud;

- Predica en tono didáctico, como un superior a los inferiores;

- Actúa con autoridad sobre las personas en asuntos espirituales.

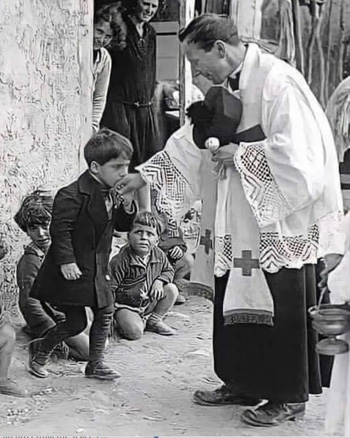

Un terrible acto de 'clericalismo' según los progresistas

La principal reprimenda dirigida al clero tradicional fue que, al participar de una manera más cercana con la Jerarquía, tenían una posición superior al resto de los fieles en la Iglesia. Cualquiera que se niegue a adoptar la noción (esencialmente protestante) de igualdad de estatus entre el clero y los laicos está manchado con el pincel del “clericalismo”. Esta es precisamente la posición del sacerdote del Opus Dei, Mons. Cormac Burke: “La mentalidad clerical considera al clero como superior, con un estatus superior en la vida de la Iglesia; y los laicos como inferiores, en una posición subordinada.” (1)

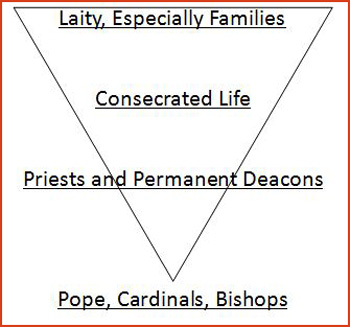

Una manía de invertir la pirámide milenaria

Este es el sistema de dos niveles descrito por el Papa Pío X en el que sólo la Jerarquía tiene el derecho y la autoridad para gobernar, y en el que los laicos tienen el deber de “dejarse conducir, y como un rebaño dócil, seguir la pastores”. (2) El Papa cita a San Cipriano en el sentido de que los primeros cristianos entendieron que este arreglo superior-inferior se basaba en la Ley Divina.

Pero, ¿qué pasa si los pastores quieren revolucionar la Constitución, “invertir el triángulo”, cambiar la Iglesia de una monarquía a una democracia, como exigen los progresistas del Vaticano II, e incluir la los laicos en el gobierno de la Iglesia? ¿Deberían los fieles seguirlos como un rebaño dócil para contravenir la Ley Divina?

Ciertamente, esta no era la intención del Papa Pío X, ya que violaría la ley de no contradicción. Más bien, es en las declaraciones de los obispos progresistas en el Vaticano II, según consta en las Acta Synodalia, donde encontramos amplia confirmación de que el desprecio por la Ley Divina se manifestó claramente entre un número significativo de prelados influyentes y sus expertos asesores que querían subvertir la Constitución de la Iglesia.

Los documentos del Concilio resultantes, que estaban contaminados con esta tendencia subversiva, tuvieron el efecto de llevar a los fieles a una batalla continua y profundamente divisiva entre la tradición católica y las fuerzas rivales del progresismo en la Iglesia.

Lecciones de la historia

Podemos ver la misma Teoría del Conflicto funcionando en la historia de todos los levantamientos políticos desde el destierro del estadista, Aristides en el siglo V a.C., líder del partido aristocrático en Atenas, hasta todas las revoluciones de inspiración marxista de los tiempos modernos, que buscaban destruir lo que consideraban una sociedad intolerablemente desigual.

El destino de Aristides, (conocido por todos como "Aristides el Justo"), quien fue desterrado de Atenas c. 482 a.C. simplemente por ser considerado “más justo” que otros, comparte un punto importante de similitud con la animosidad posterior al Vaticano II hacia el sistema desigual de dos niveles de la Iglesia. Según el historiador griego Plutarco, Arístides sufrió el exilio a manos de los ciudadanos atenienses debido a su “desprecio envidioso por su reputación” y porque estaban “enfadados con aquellos que se elevaban sobre la multitud en nombre y reputación”.

Un hombre se refirió de esta forma sobre Arístides: 'Ni siquiera conozco a Arístides, pero estoy cansado de escuchar que en todas partes lo llamen El Justo’

El “ostracismo” era una antigua práctica griega utilizada por los ciudadanos atenienses que ejercían sus derechos democráticos, lo que les permitía desterrar a cualquier ciudadano destacado de la ciudad durante 10 años. El nombre deriva del ostrakon (plural ostraka), un fragmento de cerámica en el que los atenienses grababan el nombre de la persona que querían exiliar, como una forma de emitir votos.

Plutarco relata un incidente divertido que sucedió durante la votación; su relevancia para las sociedades modernas se puede comprender fácilmente porque arroja luz sobre las fuentes de la naturaleza humana que provocan sentimientos de envidia hacia las personas de mayor virtud o posición superior:

“Ahora bien, en el momento del que estaba hablando, mientras los votantes estaban inscribiendo su ostraka, se dice que un tipo iletrado y completamente grosero entregó su ostrakon a Arístides, a quien lo tomó por uno de la multitud común y le pidió que escribiera Arístides en él. Asombrado, le preguntó al hombre qué mal le había hecho Arístides. 'Ninguno en absoluto', fue la respuesta, 'Ni siquiera conozco a Arístides, pero estoy cansado de escuchar que en todas partes lo llamen 'El Justo' "(4)

Hay aquí un paralelismo evidente con el destino de los sacerdotes hoy, que son condenados como “clericalistas” simplemente por ser clérigos y, por lo tanto, de un estatus superior al de sus subordinados, los laicos. Al igual que con el asunto Arístides, el mismo patrón de animosidad se produjo durante la reforma de la Constitución del Vaticano II cuando los progresistas votaron a favor del ostracismo de la Tradición.

Hubo la misma negativa a reconocer la eminencia, como en "No eres más alto que el resto de nosotros" (lo que resultó en la difuminación de la distinción entre el sacerdocio y los laicos); las mismas acusaciones de opresión bajo los poderes gobernantes (Aristides fue acusado del crimen supremo en una democracia: querer convertirse en rey); las mismas técnicas de agitación para poner al pueblo en contra de sus líderes (Aristides fue calumniado por su rival político, Temístocles, quien contó con el apoyo de las clases bajas contra la nobleza ateniense); el mismo enmascaramiento hipócrita de la envidia bajo la bandera de la “justicia” y la “igualdad”; y la misma experiencia de Schadenfreude (5) que en la Iglesia moderna tomó la forma de un cierto deleite en derribar al sacerdote de su pedestal.

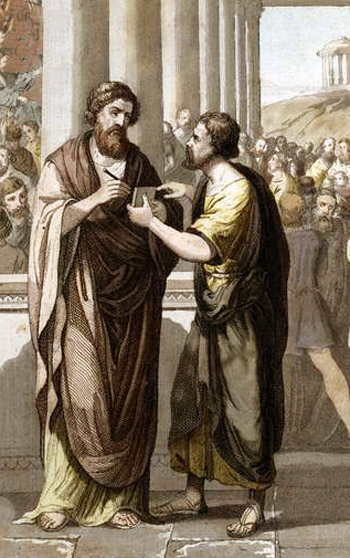

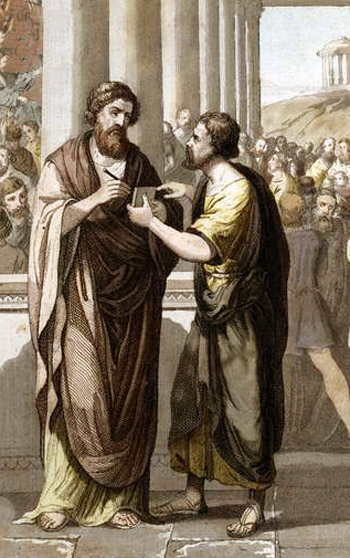

A partir de estas consideraciones, no es difícil ver cómo la devaluación del estatus superior del sacerdote inspirada por el Vaticano II fue de la misma época que ese vicio de la naturaleza humana que fue la causa próxima de la Pasión de Nuestro Señor: “Fue por envidia de que los principales sacerdotes lo hubieran entregado.” (Mt 27,18)

La envidia motivó el odio de los fariseos

hacia Nuestro Señor Jesucristo

No es de extrañar, por lo tanto, que tras el Concilio tales actitudes anticlericales se tradujeran en la pérdida, sustracción o entorpecimiento de aquellos bienes que correspondían al clero ordenado: sus Órdenes Menores preliminares, su relación única con la Eucaristía, su función exclusiva en el santuario, la reverencia y deferencia con que eran tratados por los laicos. Todos estos privilegios del clero se convirtieron en objeto de la ira iconoclasta.

Mientras que este tipo de prejuicio anticlerical alguna vez se esperaba solo de herejes e ideólogos seculares opuestos al catolicismo, ahora es dolorosamente obvio que los mismos católicos están abiertamente involucrados en el ataque contra el sacerdocio ordenado.

Continuará...

- Cormac Burke, 'La libertad y responsabilidad de los laicos', Homiletic and Pastoral Review, julio de 1993, pp. 19-20.

- Pío X, Vehementer Nos (1906) § 8.

- Plutarco, Vidas, traducción de Bernadotte Perrin, 11 volúmenes, vol. 2: Temístocles y Camilo. Aristides and Cato Major, Cimon and Lucullus, Londres: Harvard University Press, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914, pp. 231 233-235.

- Ibíd., págs. 233, 235.

- Una mezcla de emociones experimentadas por los envidiosos que obtienen satisfacción al presenciar el fracaso o la humillación de otros (del alemán Schaden que significa "daño, daño, lesión" y Freude que significa “alegría”)

- Summa Theologica, II-II, 36.2: “nos afligimos por el bien de un hombre en la medida en que su bien supera al nuestro; esto es envidia propiamente hablando y es siempre pecaminoso.”

Publicado el 22 de septiembre de 2022

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |