Asuntos Tradicionalistas

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Misa Dialogada - CXXXVII

Desaparición repentina de la “tradición manualista”

después del Vaticano II

Cómo exactamente los Manuales teológicos repentinamente cayeron en desgracia, y fueron igual y repentinamente reducidos al estado de meras quisquiliae (cosas inútiles que deben descartarse) después de haber sido santificadas por una larga tradición, no es un tema generalmente conocido hoy en día, ni siquiera entre los tradicionalistas. Podemos dar por cierto que la mayoría de los sacerdotes no saben cómo y por qué desaparecieron, y muestran poco interés en averiguarlo. Al parecer, prefieren aferrarse a los retratos poco halagadores repetidos por los progresistas que describen los Manuales como una mancha en el panorama intelectual de la Iglesia.

Pocos católicos de tendencia conservadora post-Vaticano II se dan cuenta de que el P. Joseph Ratzinger, en colaboración con el P. Karl Rahner fue el principal teólogo en los primeros meses del Concilio que rechazó la mayoría de los borradores iniciales de los documentos y exigió que fueran reelaborados para adaptarlos a las sensibilidades modernas. Es importante tener presente que estos borradores oficiales, elaborados por la Comisión Central Preparatoria bajo la dirección del Card. Ottaviani, se basaron en las auténticas doctrinas católicas enseñadas por los Papas anteriores al Vaticano II, que representaban de manera crucial el contenido teológico de los libros de texto o manuales del seminario.

Antes de continuar, es necesario hacer una observación más sobre este tema. Ratzinger estaba en la posición más fuerte para ejercer una inmensa influencia en la formulación de los documentos del Concilio porque era el asesor personal del cardenal Frings, jefe de la Conferencia Episcopal Alemana. Rechazó la “tradición manualista” a favor de una mayor libertad teológica para reformular la doctrina. En su Introducción al cristianismo, publicada por primera vez en 1968, hizo una dura denuncia de las “fórmulas fijas” (una referencia indirecta a la “tradición manualista”) y su uso para transmitir la fe a las generaciones futuras. Ratzinger afirmó:

Antes de continuar, es necesario hacer una observación más sobre este tema. Ratzinger estaba en la posición más fuerte para ejercer una inmensa influencia en la formulación de los documentos del Concilio porque era el asesor personal del cardenal Frings, jefe de la Conferencia Episcopal Alemana. Rechazó la “tradición manualista” a favor de una mayor libertad teológica para reformular la doctrina. En su Introducción al cristianismo, publicada por primera vez en 1968, hizo una dura denuncia de las “fórmulas fijas” (una referencia indirecta a la “tradición manualista”) y su uso para transmitir la fe a las generaciones futuras. Ratzinger afirmó:

“[La incredulidad moderna] no puede contrarrestarse simplemente aferrándose al metal precioso de las fórmulas fijas de antaño, porque entonces seguirá siendo sólo un trozo de metal, una carga en lugar de algo que ofrezca, en virtud de su valor, la posibilidad de la verdadera libertad. Aquí es donde entra en juego el presente libro: su objetivo es ayudar a comprender de nuevo la fe como algo que hace posible la verdadera humanidad en el mundo de hoy, exponer la fe sin convertirla en una pequeña moneda de palabras vacías que trabajan dolorosamente para ocultar un completo vacío espiritual". 1

Como menciona en el prefacio, el contenido de su libro fue tomado de una conferencia que dio en 1967 a estudiantes de la Universidad de Tubinga. Paradójicamente, parece haber considerado que su papel como profesor era enseñarles a despreciar la “tradición manualista”. Porque ese es el resultado inevitable de denunciar como un anacronismo ahora inútil, el venerado (y altamente exitoso) método escolástico de la Iglesia de enseñar la fe con manuales.

La complicidad de Ratzinger con la revolución radical

La conferencia del profesor Ratzinger de 1967 no podría haber llegado en peor momento. Alemania Occidental estuvo en el centro del movimiento de protesta estudiantil europeo de 1968 y fue dirigida por el activista estudiantil socialista Rudi Dutschke. (Fue él, dicho sea de paso, quien formuló el término “Larga Marcha a través de las Instituciones” como una estrategia para trabajar contra las estructuras establecidas mientras se trabaja dentro de ellas).

Muchos estudiantes de la Universidad de Tubinga, donde Ratzinger había estado enseñando durante dos años, estuvieron entre los que tomaron parte activa en los disturbios generalizados, la violencia y la destrucción que les siguieron. Su rebelión fue esencialmente una protesta contra todas las “fórmulas fijas” (como las que se encuentran, por ejemplo, en Humanae vitae, que fue un punto particularmente conflictivo) que apoyaban las estructuras patriarcales, los patrones de estilo de vida y la moral tradicional que operaban en la Iglesia y sociedad.

Como en conferencias similares de sus contemporáneos, el P. Karl Rahner y el P. Hans Küng, el profesor Ratzinger estaba lleno de cientos de estudiantes radicalizados atraídos como abejas a un tarro de miel. (Más tarde, puso un brillo eufemístico a su popularidad entre los estudiantes diciendo que ellos “reaccionaron con entusiasmo al nuevo tono que creían escuchar en mis palabras”). 2

Pero lo que realmente escucharon y ante lo que reaccionaron fue una nueva orientación teológica que justificaría sus impulsos revolucionarios de “liberación” y los ayudaría a diseñar planes para una acción radical en la Iglesia y la sociedad. Está ampliamente demostrado que este tipo de rebelión antiautoridad fue el caso del movimiento estudiantil alemán de 1968.3 Además, no se puede negar que los tres teólogos progresistas – Ratzinger, Rahner y Küng – explotaron el desarrollo intelectual relativamente inmaduro y la credulidad de los jóvenes, en su mayoría todavía adolescentes, para infundirles propaganda antitradicional presentando la opinión como un hecho.

Pero lo que realmente escucharon y ante lo que reaccionaron fue una nueva orientación teológica que justificaría sus impulsos revolucionarios de “liberación” y los ayudaría a diseñar planes para una acción radical en la Iglesia y la sociedad. Está ampliamente demostrado que este tipo de rebelión antiautoridad fue el caso del movimiento estudiantil alemán de 1968.3 Además, no se puede negar que los tres teólogos progresistas – Ratzinger, Rahner y Küng – explotaron el desarrollo intelectual relativamente inmaduro y la credulidad de los jóvenes, en su mayoría todavía adolescentes, para infundirles propaganda antitradicional presentando la opinión como un hecho.

La determinación de Ratzinger de librar a la Iglesia de las “fórmulas fijas” –que habían actuado como pegamento que ayudó a evitar la disolución del orden cristiano de la Iglesia y la sociedad– no hizo nada para mejorar la situación, e incluso ayudó a avivar las llamas de la revuelta. Con tanta presión de todos lados por la “emancipación”, la Universidad descendió a una vorágine de revolución y teología radical, y la propia Iglesia hizo lo mismo, fracturando en el proceso sus vínculos comunes de tradición, costumbre, cultura y moralidad.

Esta lamentable situación puede verse como una etapa temprana de la abdicación de la autoridad clerical que se haría evidente después del Vaticano II, cuando obispos y sacerdotes simplemente abandonaron la lucha por los intereses de la Iglesia contra las fuerzas revolucionarias que buscaban destruirla. No cabe duda de que mantener la “tradición manualista” con sus “fórmulas fijas” habría sido un baluarte seguro contra la revolución.

Crisis de mediados del siglo XX de la 'tradición manualista' en los seminarios

Refiriéndose a sus propios días de seminario, Ratzinger comentó con evidente entusiasmo:

“Todos nosotros vivíamos con un sentimiento de cambio radical que ya había surgido en la década de 1920, el sentido de una teología que tenía el coraje de plantear nuevas preguntas y una espiritualidad que estaba acabando con lo que era polvoriento y obsoleto y conducía a una nueva alegría en la redención”. 4

Su opinión de que se necesitaba “coraje” para plantear nuevas cuestiones teológicas a principios del siglo XX era una crítica velada a las autoridades romanas que intentaban aplastar el movimiento modernista. No distinguió entre cuestionar como indagación (como en “fe que busca comprensión”) y cuestionar como que implica duda o incredulidad absoluta (como en el escepticismo del modernismo hacia la doctrina aceptada). Y, sin embargo, la distinción es crucial, porque la comprensión correcta y la comunicación efectiva de ideas siempre implican hacer distinciones cuidadosas, como habría encontrado en los Manuales, si los hubiera consultado.

El objetivo de la opinión de Ratzinger era obviamente reforzar el habitual estereotipo progresista de la Iglesia anterior al Vaticano II como una institución obstinada y oscurantista que apuntala un régimen tiránico que suprime el progreso sofocando la investigación y el debate intelectual. Lo que no supo apreciar fue que el método escolástico de explicar la fe no requiere que la gente se abstenga de hacer preguntas; pero sí les impide llegar a respuestas erróneas en el sentido de sacar conclusiones de premisas iniciales que sean contrarias a los principios católicos.

De hecho, el valor y la legitimidad de hacer preguntas siempre fueron reconocidos en la Iglesia. La Summa de Santo Tomás, por ejemplo, se construyó con ese método: contiene tantas preguntas como respuestas. Luego estaban las grandes Disputationes y Controversiae del período de la Contrarreforma que se dedicaban a resolver quaestiones sobre cuestiones teológicas. Esto dio lugar a mucho fermento y debate intelectual, todo lo cual quedó subsumido en el sistema escolástico y finalmente emergió en la "tradición manualista".

La Iglesia, entonces, nunca tuvo problema en las preguntas. El problema estaba en los teólogos progresistas que no querían escuchar las respuestas.

La atracción de Ratzinger por la teología progresista de principios de siglo (del tipo denominado “modernismo” y condenado por el Papa Pío X) fue un factor clave en su rechazo de las “fórmulas fijas” que se encuentran en los viejos y polvorientos tomos de la “tradición manualista”. Al igual que sus compañeros neomodernistas, estaba embriagado por la perspectiva de nuevos y emocionantes avances en teología que le abrirían nuevos horizontes y satisfarían su sed de novedad. El principal teólogo progresista de la época de Pío XII, Henri de Lubac SJ, alcanzó a sus ojos la categoría de héroe: él también despreciaba la tradición escolástica que se encuentra en los Manuales.

Luego estaban los compañeros de De Lubac –Chenu, Congar, Daniélou– que fueron particularmente activos en la promoción de la teología del “recurso” en la década de 1940, y con quienes Ratzinger colaboró en sus esfuerzos por destronar la teología escolástica.

Luego estaban los compañeros de De Lubac –Chenu, Congar, Daniélou– que fueron particularmente activos en la promoción de la teología del “recurso” en la década de 1940, y con quienes Ratzinger colaboró en sus esfuerzos por destronar la teología escolástica.

Además de estas fuentes francesas, Ratzinger añade en sus Memorias una Pléiade de teólogos progresistas alemanes contemporáneos 5 que ejercieron una influencia fundamental en su pensamiento. Entre ellos se encontraba su profesor de Teología Moral, el padre Richard Egenter y sus colegas, que buscaban “poner fin al dominio de la casuística y la ley natural” y permitirían a la gente “repensar la moral sobre la base del seguimiento de Cristo”. 6

Como era de esperar, todos rechazaron la “tradición manualista”. La Biblia, más que la Tradición, sería la regla rectora. Esto es suficiente para mostrar que Ratzinger pertenecía a una franja bohemia de teólogos que se unieron contra la teología dominante y desafiaron los valores dominantes en la Iglesia.

La conclusión ineludible es que Ratzinger estaba del lado de los neomodernistas que quieren libertad académica ilimitada en lugar de someter sus intelectos a la autoridad de la Jerarquía en cuestiones de doctrina revelada. Esto lo confirma su observación de que, al comienzo del Concilio, el Papa Juan XXIII “por la fuerza de su personalidad” había infundido a los debates una “santa libertad” y un nuevo espíritu de “apertura y franqueza”. Vio este cambio como una catarsis en el sentido de que “la neurosis antimodernista que había paralizado una y otra vez a la Iglesia desde principios de siglo aquí parecía estar acercándose a una cura”. 7

La imagen que Ratzinger tiene del Papa Juan XXIII como una figura sonriente y paternal que brinda generosas muestras de buen humor en el Concilio tiene un significado más profundo. En primer lugar, fue el propio Ratzinger quien jugó un papel importante antes y durante el Concilio para cambiar su tono, humor y orientación. 8 Hay evidencia de que él solo trazó el modelo para el Vaticano II cuando compuso una conferencia que el Card. Frings la pronunciase en Génova en noviembre de 1961 una conferencia sobre la Iglesia en el mundo moderno. 9

La imagen que Ratzinger tiene del Papa Juan XXIII como una figura sonriente y paternal que brinda generosas muestras de buen humor en el Concilio tiene un significado más profundo. En primer lugar, fue el propio Ratzinger quien jugó un papel importante antes y durante el Concilio para cambiar su tono, humor y orientación. 8 Hay evidencia de que él solo trazó el modelo para el Vaticano II cuando compuso una conferencia que el Card. Frings la pronunciase en Génova en noviembre de 1961 una conferencia sobre la Iglesia en el mundo moderno. 9

Según el biógrafo de Frings, el p. Norbert Trippen, Juan XXIII, quedó tan satisfecho con su contenido y su tono que lo declaró totalmente compatible con sus propias intenciones para el Concilio. 10 Cualquiera que lea la Conferencia (también está disponible una traducción de pasajes seleccionados al inglés) 11 puede ver una correspondencia exacta en varios puntos con el texto del discurso de apertura de Juan XXIII, Gaudet Mater Ecclesia. Curiosamente, Romano Amerio, que era peritus en el Concilio, detectó la mano de un autor oculto:

"El discurso de apertura del Concilio... es un documento complejo, y hay evidencia de que esto se debe en parte a que el pensamiento del Papa se presenta en una versión influenciada por otra persona". 12

Al parecer, desconocía el papel de Ratzinger como escritor fantasma del documento.

En segundo lugar, y aún más significativamente, la imagen artificial de Ratzinger de un alegre Juan XXIII fue un pretexto para presentar bajo una luz negativa la “vieja política de exclusividad, condena y defensa” de la Iglesia que, según él, “conducía a una negación casi neurótica de todo lo que era nuevo.” 13 Era su manera de decir que el Vaticano II era la “cura” para la Tradición.

Continuará ...

Pocos católicos de tendencia conservadora post-Vaticano II se dan cuenta de que el P. Joseph Ratzinger, en colaboración con el P. Karl Rahner fue el principal teólogo en los primeros meses del Concilio que rechazó la mayoría de los borradores iniciales de los documentos y exigió que fueran reelaborados para adaptarlos a las sensibilidades modernas. Es importante tener presente que estos borradores oficiales, elaborados por la Comisión Central Preparatoria bajo la dirección del Card. Ottaviani, se basaron en las auténticas doctrinas católicas enseñadas por los Papas anteriores al Vaticano II, que representaban de manera crucial el contenido teológico de los libros de texto o manuales del seminario.

Rahner y Ratzinger colaboraron para socavar la perenne doctrina católica

“[La incredulidad moderna] no puede contrarrestarse simplemente aferrándose al metal precioso de las fórmulas fijas de antaño, porque entonces seguirá siendo sólo un trozo de metal, una carga en lugar de algo que ofrezca, en virtud de su valor, la posibilidad de la verdadera libertad. Aquí es donde entra en juego el presente libro: su objetivo es ayudar a comprender de nuevo la fe como algo que hace posible la verdadera humanidad en el mundo de hoy, exponer la fe sin convertirla en una pequeña moneda de palabras vacías que trabajan dolorosamente para ocultar un completo vacío espiritual". 1

Como menciona en el prefacio, el contenido de su libro fue tomado de una conferencia que dio en 1967 a estudiantes de la Universidad de Tubinga. Paradójicamente, parece haber considerado que su papel como profesor era enseñarles a despreciar la “tradición manualista”. Porque ese es el resultado inevitable de denunciar como un anacronismo ahora inútil, el venerado (y altamente exitoso) método escolástico de la Iglesia de enseñar la fe con manuales.

La complicidad de Ratzinger con la revolución radical

La conferencia del profesor Ratzinger de 1967 no podría haber llegado en peor momento. Alemania Occidental estuvo en el centro del movimiento de protesta estudiantil europeo de 1968 y fue dirigida por el activista estudiantil socialista Rudi Dutschke. (Fue él, dicho sea de paso, quien formuló el término “Larga Marcha a través de las Instituciones” como una estrategia para trabajar contra las estructuras establecidas mientras se trabaja dentro de ellas).

Muchos estudiantes de la Universidad de Tubinga, donde Ratzinger había estado enseñando durante dos años, estuvieron entre los que tomaron parte activa en los disturbios generalizados, la violencia y la destrucción que les siguieron. Su rebelión fue esencialmente una protesta contra todas las “fórmulas fijas” (como las que se encuentran, por ejemplo, en Humanae vitae, que fue un punto particularmente conflictivo) que apoyaban las estructuras patriarcales, los patrones de estilo de vida y la moral tradicional que operaban en la Iglesia y sociedad.

Como en conferencias similares de sus contemporáneos, el P. Karl Rahner y el P. Hans Küng, el profesor Ratzinger estaba lleno de cientos de estudiantes radicalizados atraídos como abejas a un tarro de miel. (Más tarde, puso un brillo eufemístico a su popularidad entre los estudiantes diciendo que ellos “reaccionaron con entusiasmo al nuevo tono que creían escuchar en mis palabras”). 2

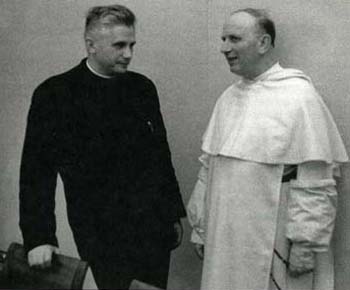

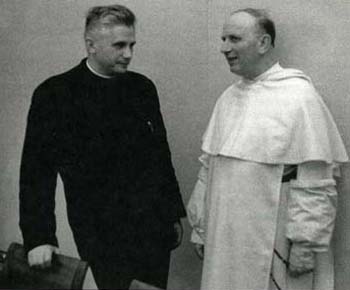

Fr. Ratzinger y Card. Frings escucha a Hans Maier,

Ministro de Educación de Baviera

La determinación de Ratzinger de librar a la Iglesia de las “fórmulas fijas” –que habían actuado como pegamento que ayudó a evitar la disolución del orden cristiano de la Iglesia y la sociedad– no hizo nada para mejorar la situación, e incluso ayudó a avivar las llamas de la revuelta. Con tanta presión de todos lados por la “emancipación”, la Universidad descendió a una vorágine de revolución y teología radical, y la propia Iglesia hizo lo mismo, fracturando en el proceso sus vínculos comunes de tradición, costumbre, cultura y moralidad.

Esta lamentable situación puede verse como una etapa temprana de la abdicación de la autoridad clerical que se haría evidente después del Vaticano II, cuando obispos y sacerdotes simplemente abandonaron la lucha por los intereses de la Iglesia contra las fuerzas revolucionarias que buscaban destruirla. No cabe duda de que mantener la “tradición manualista” con sus “fórmulas fijas” habría sido un baluarte seguro contra la revolución.

Crisis de mediados del siglo XX de la 'tradición manualista' en los seminarios

Refiriéndose a sus propios días de seminario, Ratzinger comentó con evidente entusiasmo:

“Todos nosotros vivíamos con un sentimiento de cambio radical que ya había surgido en la década de 1920, el sentido de una teología que tenía el coraje de plantear nuevas preguntas y una espiritualidad que estaba acabando con lo que era polvoriento y obsoleto y conducía a una nueva alegría en la redención”. 4

Su opinión de que se necesitaba “coraje” para plantear nuevas cuestiones teológicas a principios del siglo XX era una crítica velada a las autoridades romanas que intentaban aplastar el movimiento modernista. No distinguió entre cuestionar como indagación (como en “fe que busca comprensión”) y cuestionar como que implica duda o incredulidad absoluta (como en el escepticismo del modernismo hacia la doctrina aceptada). Y, sin embargo, la distinción es crucial, porque la comprensión correcta y la comunicación efectiva de ideas siempre implican hacer distinciones cuidadosas, como habría encontrado en los Manuales, si los hubiera consultado.

El objetivo de la opinión de Ratzinger era obviamente reforzar el habitual estereotipo progresista de la Iglesia anterior al Vaticano II como una institución obstinada y oscurantista que apuntala un régimen tiránico que suprime el progreso sofocando la investigación y el debate intelectual. Lo que no supo apreciar fue que el método escolástico de explicar la fe no requiere que la gente se abstenga de hacer preguntas; pero sí les impide llegar a respuestas erróneas en el sentido de sacar conclusiones de premisas iniciales que sean contrarias a los principios católicos.

De hecho, el valor y la legitimidad de hacer preguntas siempre fueron reconocidos en la Iglesia. La Summa de Santo Tomás, por ejemplo, se construyó con ese método: contiene tantas preguntas como respuestas. Luego estaban las grandes Disputationes y Controversiae del período de la Contrarreforma que se dedicaban a resolver quaestiones sobre cuestiones teológicas. Esto dio lugar a mucho fermento y debate intelectual, todo lo cual quedó subsumido en el sistema escolástico y finalmente emergió en la "tradición manualista".

La Iglesia, entonces, nunca tuvo problema en las preguntas. El problema estaba en los teólogos progresistas que no querían escuchar las respuestas.

La atracción de Ratzinger por la teología progresista de principios de siglo (del tipo denominado “modernismo” y condenado por el Papa Pío X) fue un factor clave en su rechazo de las “fórmulas fijas” que se encuentran en los viejos y polvorientos tomos de la “tradición manualista”. Al igual que sus compañeros neomodernistas, estaba embriagado por la perspectiva de nuevos y emocionantes avances en teología que le abrirían nuevos horizontes y satisfarían su sed de novedad. El principal teólogo progresista de la época de Pío XII, Henri de Lubac SJ, alcanzó a sus ojos la categoría de héroe: él también despreciaba la tradición escolástica que se encuentra en los Manuales.

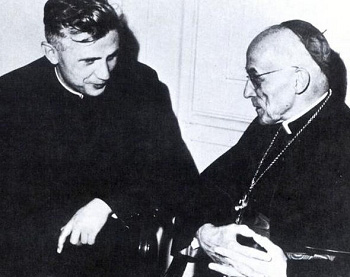

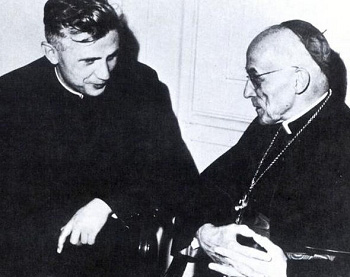

Ratzinger con el no menos radical Yves Congar.

Además de estas fuentes francesas, Ratzinger añade en sus Memorias una Pléiade de teólogos progresistas alemanes contemporáneos 5 que ejercieron una influencia fundamental en su pensamiento. Entre ellos se encontraba su profesor de Teología Moral, el padre Richard Egenter y sus colegas, que buscaban “poner fin al dominio de la casuística y la ley natural” y permitirían a la gente “repensar la moral sobre la base del seguimiento de Cristo”. 6

Como era de esperar, todos rechazaron la “tradición manualista”. La Biblia, más que la Tradición, sería la regla rectora. Esto es suficiente para mostrar que Ratzinger pertenecía a una franja bohemia de teólogos que se unieron contra la teología dominante y desafiaron los valores dominantes en la Iglesia.

La conclusión ineludible es que Ratzinger estaba del lado de los neomodernistas que quieren libertad académica ilimitada en lugar de someter sus intelectos a la autoridad de la Jerarquía en cuestiones de doctrina revelada. Esto lo confirma su observación de que, al comienzo del Concilio, el Papa Juan XXIII “por la fuerza de su personalidad” había infundido a los debates una “santa libertad” y un nuevo espíritu de “apertura y franqueza”. Vio este cambio como una catarsis en el sentido de que “la neurosis antimodernista que había paralizado una y otra vez a la Iglesia desde principios de siglo aquí parecía estar acercándose a una cura”. 7

P. Ratzinger, secretario personal del Card. Frings

Según el biógrafo de Frings, el p. Norbert Trippen, Juan XXIII, quedó tan satisfecho con su contenido y su tono que lo declaró totalmente compatible con sus propias intenciones para el Concilio. 10 Cualquiera que lea la Conferencia (también está disponible una traducción de pasajes seleccionados al inglés) 11 puede ver una correspondencia exacta en varios puntos con el texto del discurso de apertura de Juan XXIII, Gaudet Mater Ecclesia. Curiosamente, Romano Amerio, que era peritus en el Concilio, detectó la mano de un autor oculto:

"El discurso de apertura del Concilio... es un documento complejo, y hay evidencia de que esto se debe en parte a que el pensamiento del Papa se presenta en una versión influenciada por otra persona". 12

Al parecer, desconocía el papel de Ratzinger como escritor fantasma del documento.

En segundo lugar, y aún más significativamente, la imagen artificial de Ratzinger de un alegre Juan XXIII fue un pretexto para presentar bajo una luz negativa la “vieja política de exclusividad, condena y defensa” de la Iglesia que, según él, “conducía a una negación casi neurótica de todo lo que era nuevo.” 13 Era su manera de decir que el Vaticano II era la “cura” para la Tradición.

Continuará ...

- Joseph Ratzinger, Introduction to Christianity, (original title Einführung in das Christentum) trans. J. R. Foster, Herder and Herder, 1970, pp. 11-12.

- Benedict XVI with Peter Seewald, Last Testament: In His Own Words, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016, p. 108.

- The subject of clerical patronage of the1968 student protest movement in Germany is well documented by Christian Schmidtmann, Katholische Studierende 1945-1973: Ein Beitrag zur Kultur und Sozialgeschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (Catholic Students 1945-1973: A Contribution to the Cultural and Social History of the Federal Republic of Germany), Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2005, pp. 280-282.

- Joseph Ratzinger, Milestones: Memoirs 1927-1977, trans. Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1998, p. 57.

- Ibid., pp. 49, 55; notably Frs. Richard Egenter, Michael Schmaus, Gottlieb Söhngen, Josef Pascher, Fritz Tillman, Theodor Steinbüchel, and Friedrich Wilhelm Maier.

- Ibid., p. 55.

- J. Ratzinger, Theological Highlights of Vatican II, trans. Henry Traub, Gerard Thormann, and Werner Barzel, New York: Paulist Press, 1966, p. 11.

- Benedict XVI with Peter Seewald, Last Testament, p. 130.

- ‘Kardinal Frings über das Konzil und die moderne Gedankenwelt’ (Cardinal Frings on the Council and the Modern World of Thought), Herder-Korrespondenz, vol. 16, 1961/62, pp. 168-174.

- Norbert Trippen, Josef Kardinal Frings (1887-1978): Sein Wirken Für Die Weltkirche Und Seine Letzten Bischofsjahre (His Work for the Universal Church and his Final Episcopal Years), 2 vol., vol. 2, Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2005, p. 262.

- Jared Wicks, SJ, ‘Six texts by Prof. Joseph Ratzinger as peritus before and during Vatican Council II,’ Gregorianum, vol. 89, no. 2, 2008, pp. 254-261.

- Romano Amerio, Iota Unum: A Study of Changes in the Catholic Church in the Twentieth Century, Angelus Press, 1996, p. 73.

- J. Ratzinger, Theological Highlights of Vatican II, p. 23.

Publicado el 9 de abril de 2024

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |