Asuntos Tradicionalistas

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Misa Dialogada - CXLII

El Legado Anti-Escéptico de Ratzinger

Ratzinger fue uno de los teólogos progresistas del siglo XX que buscaban explicaciones alternativas para la Presencia Eucarística que les permitieran superar las restricciones de la Metafísica Tomista a fin de satisfacer los requerimientos del mundo moderno y, especialmente, las demandas del Movimiento Ecuménico. Para lograr estos objetivos, las formulaciones perpetuamente válidas del Concilio de Trento tendrían que ser descartadas bajo el argumento de que son incomprensibles en el mundo de la ciencia moderna y la “fraternidad ecuménica”.

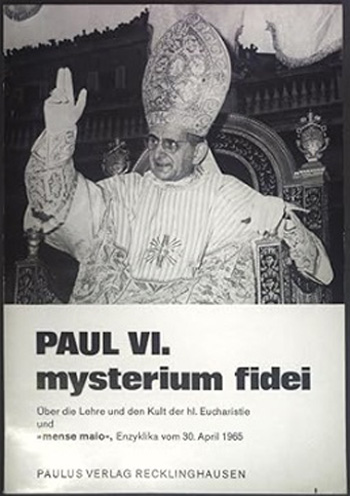

Antes de examinar la contribución de Ratzinger al aggiornamento en el área de la teología eucarística, es oportuno recordar una encíclica papal casi olvidada: Mysterium Fidei (1965) emitida por Pablo VI justo antes del cierre del Vaticano II. En ella, afirmó que “no es permisible ... discutir el misterio de la transubstanciación sin mencionar lo que el Concilio de Trento tenía que decir sobre la maravillosa conversión de toda la sustancia del pan en el Cuerpo y de toda la sustancia del vino en la Sangre de Cristo”. (§ 11)

Para ilustrar su punto sobre la necesidad de usar la terminología correcta “respecto a la fe en las cosas más sublimes,” citó la severa advertencia de San Agustín (Ciudad de Dios, X, 23) sobre este asunto:

“Pero tenemos que hablar de acuerdo con una regla fija, para que una falta de moderación en nuestro discurso no dé lugar a alguna opinión irreverente sobre las cosas representadas por las palabras”. (§ 23)

“Pero tenemos que hablar de acuerdo con una regla fija, para que una falta de moderación en nuestro discurso no dé lugar a alguna opinión irreverente sobre las cosas representadas por las palabras”. (§ 23)

El problema para Ratzinger (quien afirmaba ser un devoto de San Agustín) era que usar fórmulas fijas no era aceptable: prefería, como veremos, dejar que su imaginación se expandiera libremente sobre formas de describir el “Misterio de la Fe” que apelaran al hombre moderno.

Aquí la sabiduría de San Agustín desmiente la falsa dicotomía del Vaticano II entre la verdadera doctrina y el lenguaje en el que se expresa. La correcta redacción siempre fue considerada esencial por la Iglesia para garantizar el verdadero significado de la transubstanciación, como afirma Mysterium Fidei:

“Y así, la regla del lenguaje que la Iglesia ha establecido a través del largo trabajo de siglos, con la ayuda del Espíritu Santo, y que ha confirmado con la autoridad de los Concilios, y que ha sido más de una vez la divisa y el estandarte de la fe ortodoxa, debe ser religiosamente preservada, y nadie puede presumir de cambiarla a su antojo o bajo el pretexto de nuevo conocimiento. ¿Quién toleraría que las fórmulas dogmáticas usadas por los concilios ecuménicos para los misterios de la Santísima Trinidad y la Encarnación sean juzgadas como ya no adecuadas para los hombres de nuestros tiempos, y que otras sean imprudentemente sustituidas por ellas? De la misma manera, no puede tolerarse que un individuo, por su propia autoridad, quite algo de las fórmulas que usó el Concilio de Trento para proponer el Misterio Eucarístico para nuestra creencia”. (§ 24)

Ahora consideraremos hasta qué punto – o si en absoluto – Ratzinger cumplió con los requisitos de Mysterium Fidei sobre el tema de la transubstanciación. Uno podría tentarse a pensar que todo está bien porque usó el término transubstanciación en más de una ocasión, como por ejemplo en su libro de 2003, God is Near Us. 1 Sin embargo, la forma en que quería que se entendiera esto está envuelta en confusión, ya que solo dos páginas antes había referido al lector a Die Eucharistische Gegenwart (1967) de Edward Schillebeeckx para apoyar su argumento. Schillebeeckx propuso “transignificación” – que fue específicamente condenada por Pablo VI en Mysterium Fidei (§ 11) – para reemplazar la transubstanciación porque creía que la “dimensión ontológica... puede estar abierta a una interpretación diferente a la de la Escolástica”. 2

Ahí radica el problema. La palabra sustancia en la Metafísica Escolástica tiene un significado diferente del mismo término usado en la física moderna. Así que, incluso cuando los teólogos progresistas usan la palabra transubstanciación, no hay garantía de conformidad con la doctrina católica. En su léxico, podría y a menudo significa que lo que cambia durante la Consagración no es la sustancia (entendida en términos Escolásticos) del pan y del vino, sino su significado para el receptor.

Ratzinger aprovechó el desarrollo de la semántica lexical en tiempos modernos para justificar deshacerse de las categorías aristotélicas de sustancia y accidentes que habían servido a la Iglesia durante siglos, sugiriendo que ya no eran útiles:

Ratzinger aprovechó el desarrollo de la semántica lexical en tiempos modernos para justificar deshacerse de las categorías aristotélicas de sustancia y accidentes que habían servido a la Iglesia durante siglos, sugiriendo que ya no eran útiles:

“En el curso del desarrollo del pensamiento filosófico y las ciencias naturales, el concepto de sustancia ha cambiado esencialmente (‘essenzialmente mutato’), al igual que la concepción de lo que, en el pensamiento aristotélico, había sido designado por ‘accidente.’ El concepto de sustancia, que antes se aplicaba a toda realidad consistente en sí misma, se refería cada vez más a lo que es físicamente esquivo: a la molécula, al átomo y a las partículas elementales, y hoy sabemos que también estas no representan una ‘sustancia’ última, sino una estructura de relaciones. Con esto surgió una nueva tarea para la filosofía cristiana. La categoría fundamental de toda realidad en términos generales ya no es sustancia, sino relación”. 3

Como es costumbre con las “explicaciones” neo-modernistas, reina la confusión. Las categorías aristotélicas pertenecen a la “filosofía perenne” de la Iglesia y nunca han “cambiado esencialmente,” por lo que siguen siendo válidas y útiles para hoy y en el futuro. Permanecen inafectadas por los avances en el ámbito de la ciencia.

Personalismo de Martin Buber y la ‘teología de la relación’

El énfasis de Ratzinger en una teología de “relación” en lugar de “ser” como medio para explicar la naturaleza de Dios ilustra los peligros de apartarse de la Metafísica Escolástica. Describió a Dios en términos “personalistas” como una relación, pero sin dirigir la inteligencia humana a conocerlo como la fuente de la Verdad, o la necesidad de primero alinear nuestras mentes con la realidad objetiva antes de poder experimentar verdaderas relaciones con Dios o con los demás.

El énfasis de Ratzinger en una teología de “relación” en lugar de “ser” como medio para explicar la naturaleza de Dios ilustra los peligros de apartarse de la Metafísica Escolástica. Describió a Dios en términos “personalistas” como una relación, pero sin dirigir la inteligencia humana a conocerlo como la fuente de la Verdad, o la necesidad de primero alinear nuestras mentes con la realidad objetiva antes de poder experimentar verdaderas relaciones con Dios o con los demás.

Aquí vemos una similitud con la “teoría de la relación” del filósofo judío Martin Buber, a quien Ratzinger, en sus propias palabras, “reverenciaba mucho... como el gran representante del Personalismo, el principio Yo-Tú”. 4 Afirmó en varias ocasiones que Buber ejerció una profunda influencia sobre él. Examinemos qué tipo de influencia fue esta.

Buber era un anarquista religioso con ideas utópicas para una revolución radical en la sociedad a lo largo de líneas comunistas. Sus ideas, transpuestas a la esfera política, lo hicieron extremadamente popular entre los católicos de izquierda y liberales. Su gran atractivo era que rechazaba todas las relaciones de poder y estructuras que ejercen autoridad en el sentido de que no debería haber dominación moral de una persona sobre otra. Se podría decir que en algunos aspectos el anarquismo espiritual de Buber iba de la mano con la imagen “piramidal invertida” inspirada en el Vaticano II. Como resultado de adoptar la filosofía del Personalismo de Buber, Ratzinger permitió que ideas socialistas y anarquistas se infiltraran en la Iglesia Católica.

Una nueva teología eucarística

Si nos preguntamos por qué, siempre que Ratzinger abordó la cuestión de la transubstanciación en sus propios escritos teológicos, no dio cuenta adecuada del concepto como exige Mysterium Fidei, la explicación proviene de una fuente de primera mano, sus propias palabras:

“Podemos notar con gratitud que en el siglo pasado se nos ha dado un nuevo y amplio punto de partida, también desde una perspectiva ecuménica, para una teología en profundidad de la Eucaristía, que ciertamente aún necesita ser meditada, vivida y sufrida”. 5 [Énfasis añadido]

La referencia a un nuevo punto de partida para la teología eucarística es difícil de conciliar con su previamente promocionada “hermenéutica de la continuidad,” y es una admisión de cambio doctrinal en favor del “ecumenismo”. Es evidente que esta teología no provino de la Tradición. Su referencia al siglo pasado sitúa la fuente de las nuevas ideas en la “Nueva Teología” que introdujo el Neo-Modernismo en la Iglesia y la instaló en un lugar de honor en el Vaticano II.

Esto hizo extremadamente difícil, si no imposible, para cualquiera que adoptara la nueva teología eucarística – y Ratzinger lo hizo, como dijo, “con gratitud” – transmitir la enseñanza tradicional de la Iglesia sobre la Eucaristía de una manera reconociblemente católica, incluso si la aceptaban internamente.

Por ejemplo, en el siguiente pasaje tomado de su libro, God Is Near Us, Ratzinger da la siguiente explicación de lo que ocurre en la Consagración:

“Hay algo nuevo allí que no estaba antes. Conocer sobre una transformación es parte de la fe eucarística más básica. Por lo tanto, no puede ser el caso que el Cuerpo de Cristo venga a añadirse al pan, como si pan y Cuerpo fueran dos cosas similares que pudieran existir como dos ‘sustancias,’ de la misma manera, lado a lado.

“Se produce una transformación que afecta los dones que llevamos al tomarlos en un orden superior y los cambia, incluso si no podemos medir lo que sucede. Cuando los materiales se toman en nuestro cuerpo como alimento, o de hecho cuando cualquier material se convierte en parte de un organismo vivo, permanece igual, y sin embargo, como parte de un nuevo todo, se cambia a sí mismo. Algo similar sucede aquí. El Señor toma posesión del pan y el vino; los eleva, por así decirlo, fuera del contexto de su existencia normal a un nuevo orden; incluso si, desde un punto de vista puramente físico, permanecen igual, se han vuelto profundamente diferentes”. 6

Sin embargo, se detiene en seco y no dice exactamente en qué consiste la diferencia. Podemos ver cómo avanza típicamente hacia la verdad, luego, como se hace en un velero, reposiciona sus velas para alterar el curso, tackeando hacia atrás y hacia adelante entre posiciones católicas y luteranas, pero nunca logra alcanzar la verdad completa. La única certeza que se puede extraer de este batiburrillo de ideas confusas y confundentes es que, cualquiera sea el barco en el que navegaba el futuro Papa, no era la Barcaza de Pedro; él lo dirigía hacia los escollos del “ecumenismo” sin articular una explicación coherente de la verdad central de la transubstanciación. La reformulación de palabras en el pasaje es de gran importancia. Ninguna de las palabras usadas por Ratzinger en relación con la Eucaristía, como transubstanciación, transformación, cambio, conversión, etc., se usa de una manera que haya sido tradicionalmente entendida. Solo mantienen la cubierta exterior de los significados tradicionales.

Sin embargo, se detiene en seco y no dice exactamente en qué consiste la diferencia. Podemos ver cómo avanza típicamente hacia la verdad, luego, como se hace en un velero, reposiciona sus velas para alterar el curso, tackeando hacia atrás y hacia adelante entre posiciones católicas y luteranas, pero nunca logra alcanzar la verdad completa. La única certeza que se puede extraer de este batiburrillo de ideas confusas y confundentes es que, cualquiera sea el barco en el que navegaba el futuro Papa, no era la Barcaza de Pedro; él lo dirigía hacia los escollos del “ecumenismo” sin articular una explicación coherente de la verdad central de la transubstanciación. La reformulación de palabras en el pasaje es de gran importancia. Ninguna de las palabras usadas por Ratzinger en relación con la Eucaristía, como transubstanciación, transformación, cambio, conversión, etc., se usa de una manera que haya sido tradicionalmente entendida. Solo mantienen la cubierta exterior de los significados tradicionales.

Esto es claramente el caso en el siguiente extracto de un libro escrito por el Papa Benedicto en sus últimos años, que solicitó que se publicara después de su muerte:

“La transubstanciación, no la consubstanciación, significa transformación, conversio y no solo adición. Esta declaración se extiende mucho más allá de las ofrendas y nos dice fundamentalmente lo que es el cristianismo: es la transformación de nuestras vidas, la transformación del mundo entero en una nueva existencia”. 7

De acuerdo con este modelo que huele a teilhardianismo y la idea del Vaticano II de la Eucaristía como el “sacramento del mundo,” el énfasis ya no está en la Presencia Real, sino que se ha desplazado hacia el pueblo y su papel en la transformación de sí mismo y del mundo.

Continuará

Antes de examinar la contribución de Ratzinger al aggiornamento en el área de la teología eucarística, es oportuno recordar una encíclica papal casi olvidada: Mysterium Fidei (1965) emitida por Pablo VI justo antes del cierre del Vaticano II. En ella, afirmó que “no es permisible ... discutir el misterio de la transubstanciación sin mencionar lo que el Concilio de Trento tenía que decir sobre la maravillosa conversión de toda la sustancia del pan en el Cuerpo y de toda la sustancia del vino en la Sangre de Cristo”. (§ 11)

Para ilustrar su punto sobre la necesidad de usar la terminología correcta “respecto a la fe en las cosas más sublimes,” citó la severa advertencia de San Agustín (Ciudad de Dios, X, 23) sobre este asunto:

El problema para Ratzinger (quien afirmaba ser un devoto de San Agustín) era que usar fórmulas fijas no era aceptable: prefería, como veremos, dejar que su imaginación se expandiera libremente sobre formas de describir el “Misterio de la Fe” que apelaran al hombre moderno.

Aquí la sabiduría de San Agustín desmiente la falsa dicotomía del Vaticano II entre la verdadera doctrina y el lenguaje en el que se expresa. La correcta redacción siempre fue considerada esencial por la Iglesia para garantizar el verdadero significado de la transubstanciación, como afirma Mysterium Fidei:

“Y así, la regla del lenguaje que la Iglesia ha establecido a través del largo trabajo de siglos, con la ayuda del Espíritu Santo, y que ha confirmado con la autoridad de los Concilios, y que ha sido más de una vez la divisa y el estandarte de la fe ortodoxa, debe ser religiosamente preservada, y nadie puede presumir de cambiarla a su antojo o bajo el pretexto de nuevo conocimiento. ¿Quién toleraría que las fórmulas dogmáticas usadas por los concilios ecuménicos para los misterios de la Santísima Trinidad y la Encarnación sean juzgadas como ya no adecuadas para los hombres de nuestros tiempos, y que otras sean imprudentemente sustituidas por ellas? De la misma manera, no puede tolerarse que un individuo, por su propia autoridad, quite algo de las fórmulas que usó el Concilio de Trento para proponer el Misterio Eucarístico para nuestra creencia”. (§ 24)

Ahora consideraremos hasta qué punto – o si en absoluto – Ratzinger cumplió con los requisitos de Mysterium Fidei sobre el tema de la transubstanciación. Uno podría tentarse a pensar que todo está bien porque usó el término transubstanciación en más de una ocasión, como por ejemplo en su libro de 2003, God is Near Us. 1 Sin embargo, la forma en que quería que se entendiera esto está envuelta en confusión, ya que solo dos páginas antes había referido al lector a Die Eucharistische Gegenwart (1967) de Edward Schillebeeckx para apoyar su argumento. Schillebeeckx propuso “transignificación” – que fue específicamente condenada por Pablo VI en Mysterium Fidei (§ 11) – para reemplazar la transubstanciación porque creía que la “dimensión ontológica... puede estar abierta a una interpretación diferente a la de la Escolástica”. 2

Ahí radica el problema. La palabra sustancia en la Metafísica Escolástica tiene un significado diferente del mismo término usado en la física moderna. Así que, incluso cuando los teólogos progresistas usan la palabra transubstanciación, no hay garantía de conformidad con la doctrina católica. En su léxico, podría y a menudo significa que lo que cambia durante la Consagración no es la sustancia (entendida en términos Escolásticos) del pan y del vino, sino su significado para el receptor.

A pesar de que Ratzinger afirmaba una doctrina diferente, Pablo VI lo hizo Cardenal

“En el curso del desarrollo del pensamiento filosófico y las ciencias naturales, el concepto de sustancia ha cambiado esencialmente (‘essenzialmente mutato’), al igual que la concepción de lo que, en el pensamiento aristotélico, había sido designado por ‘accidente.’ El concepto de sustancia, que antes se aplicaba a toda realidad consistente en sí misma, se refería cada vez más a lo que es físicamente esquivo: a la molécula, al átomo y a las partículas elementales, y hoy sabemos que también estas no representan una ‘sustancia’ última, sino una estructura de relaciones. Con esto surgió una nueva tarea para la filosofía cristiana. La categoría fundamental de toda realidad en términos generales ya no es sustancia, sino relación”. 3

Como es costumbre con las “explicaciones” neo-modernistas, reina la confusión. Las categorías aristotélicas pertenecen a la “filosofía perenne” de la Iglesia y nunca han “cambiado esencialmente,” por lo que siguen siendo válidas y útiles para hoy y en el futuro. Permanecen inafectadas por los avances en el ámbito de la ciencia.

Personalismo de Martin Buber y la ‘teología de la relación’

Martin Buber, anarquista y utópico

Aquí vemos una similitud con la “teoría de la relación” del filósofo judío Martin Buber, a quien Ratzinger, en sus propias palabras, “reverenciaba mucho... como el gran representante del Personalismo, el principio Yo-Tú”. 4 Afirmó en varias ocasiones que Buber ejerció una profunda influencia sobre él. Examinemos qué tipo de influencia fue esta.

Buber era un anarquista religioso con ideas utópicas para una revolución radical en la sociedad a lo largo de líneas comunistas. Sus ideas, transpuestas a la esfera política, lo hicieron extremadamente popular entre los católicos de izquierda y liberales. Su gran atractivo era que rechazaba todas las relaciones de poder y estructuras que ejercen autoridad en el sentido de que no debería haber dominación moral de una persona sobre otra. Se podría decir que en algunos aspectos el anarquismo espiritual de Buber iba de la mano con la imagen “piramidal invertida” inspirada en el Vaticano II. Como resultado de adoptar la filosofía del Personalismo de Buber, Ratzinger permitió que ideas socialistas y anarquistas se infiltraran en la Iglesia Católica.

Una nueva teología eucarística

Si nos preguntamos por qué, siempre que Ratzinger abordó la cuestión de la transubstanciación en sus propios escritos teológicos, no dio cuenta adecuada del concepto como exige Mysterium Fidei, la explicación proviene de una fuente de primera mano, sus propias palabras:

“Podemos notar con gratitud que en el siglo pasado se nos ha dado un nuevo y amplio punto de partida, también desde una perspectiva ecuménica, para una teología en profundidad de la Eucaristía, que ciertamente aún necesita ser meditada, vivida y sufrida”. 5 [Énfasis añadido]

La referencia a un nuevo punto de partida para la teología eucarística es difícil de conciliar con su previamente promocionada “hermenéutica de la continuidad,” y es una admisión de cambio doctrinal en favor del “ecumenismo”. Es evidente que esta teología no provino de la Tradición. Su referencia al siglo pasado sitúa la fuente de las nuevas ideas en la “Nueva Teología” que introdujo el Neo-Modernismo en la Iglesia y la instaló en un lugar de honor en el Vaticano II.

Esto hizo extremadamente difícil, si no imposible, para cualquiera que adoptara la nueva teología eucarística – y Ratzinger lo hizo, como dijo, “con gratitud” – transmitir la enseñanza tradicional de la Iglesia sobre la Eucaristía de una manera reconociblemente católica, incluso si la aceptaban internamente.

Por ejemplo, en el siguiente pasaje tomado de su libro, God Is Near Us, Ratzinger da la siguiente explicación de lo que ocurre en la Consagración:

“Hay algo nuevo allí que no estaba antes. Conocer sobre una transformación es parte de la fe eucarística más básica. Por lo tanto, no puede ser el caso que el Cuerpo de Cristo venga a añadirse al pan, como si pan y Cuerpo fueran dos cosas similares que pudieran existir como dos ‘sustancias,’ de la misma manera, lado a lado.

“Se produce una transformación que afecta los dones que llevamos al tomarlos en un orden superior y los cambia, incluso si no podemos medir lo que sucede. Cuando los materiales se toman en nuestro cuerpo como alimento, o de hecho cuando cualquier material se convierte en parte de un organismo vivo, permanece igual, y sin embargo, como parte de un nuevo todo, se cambia a sí mismo. Algo similar sucede aquí. El Señor toma posesión del pan y el vino; los eleva, por así decirlo, fuera del contexto de su existencia normal a un nuevo orden; incluso si, desde un punto de vista puramente físico, permanecen igual, se han vuelto profundamente diferentes”. 6

God is Near Us de Ratzinger mezcla luteranismo con catolicismo

Esto es claramente el caso en el siguiente extracto de un libro escrito por el Papa Benedicto en sus últimos años, que solicitó que se publicara después de su muerte:

“La transubstanciación, no la consubstanciación, significa transformación, conversio y no solo adición. Esta declaración se extiende mucho más allá de las ofrendas y nos dice fundamentalmente lo que es el cristianismo: es la transformación de nuestras vidas, la transformación del mundo entero en una nueva existencia”. 7

De acuerdo con este modelo que huele a teilhardianismo y la idea del Vaticano II de la Eucaristía como el “sacramento del mundo,” el énfasis ya no está en la Presencia Real, sino que se ha desplazado hacia el pueblo y su papel en la transformación de sí mismo y del mundo.

Continuará

- J. Ratzinger, God Is Near Us, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2003, p. 87.

- Edward Schillebeeckx, The Eucharist, Nueva York: Sheed and Ward, 1968, p. 84.

- Benedict XVI, Che Cos’è il Cristianesimo?, p. 130 (versión en línea)

- Benedict XVI, Last Testament, p. 99.

- Benedict XVI, Che Cos’è il Cristianesimo?, p. 133.

- J. Ratzinger, God Is Near Us, p.86.

- Benedict XVI, Che Cos’è il Cristianesimo?, p. 132.

Publicado el 16 de septiembre de 2024

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |