Asuntos Tradicionalistas

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Misa Dialogada - CXLVIII

Objeciones al esquema en

Castidad, matrimonio, familia y la Virginidad

Este esquema, que explicaba la enseñanza perenne de la Iglesia sobre el matrimonio y temas relacionados en términos claros, sencillos y adecuadamente modestos, causó una intensa consternación entre los progresistas en vísperas del Concilio, cuando se debatía el tema. El cardenal Frings, apoyado por Ratzinger, transmitió una irritación apenas disimulada en su comentario sobre el esquema. Se quejó (se quejaron) de la inclusión de las enseñanzas de la Casti connubii de Pío XI (sobre el matrimonio cristiano) en el documento, cuestionando por qué era necesario reiterarlas e incluso ampliarlas.

Transpuesto a términos sencillos, inteligibles para el hombre moderno y hedonista, era como si Ratzinger-Frings hubiera dicho:

Dejen de hablar del Sexto Mandamiento: a la gente común no le interesan esas cosas. Lo que quieren oír de nosotros es cómo sacarle el máximo provecho a esta vida. Todas esas tonterías idealistas les resultan irrelevantes. Además, distraen de las exigencias realistas de la vida moderna: ayudar a los pobres, salvar el planeta y unir a la humanidad.

Dejen de hablar del Sexto Mandamiento: a la gente común no le interesan esas cosas. Lo que quieren oír de nosotros es cómo sacarle el máximo provecho a esta vida. Todas esas tonterías idealistas les resultan irrelevantes. Además, distraen de las exigencias realistas de la vida moderna: ayudar a los pobres, salvar el planeta y unir a la humanidad.

El siguiente comentario de Frings —influenciado, como veremos más adelante, por las reflexiones teológicas de Ratzinger— es sumamente revelador porque explica la verdadera razón por la que los Casti connubii supusieron una vergüenza para los reformadores:

En materia matrimonial («ubi de matrimonio agitur»), no se debe juzgar ni condenar («non judicando et damnando»), sino ofrecer el consuelo de la fe cristiana mostrando respeto por la tradición oriental, como hizo el Concilio de Trento, que suavizó su canon 7 sobre el matrimonio para evitar ofender a los griegos («ne Graeci offendantur»). 1 (Énfasis añadido)

Si los católicos tradicionales de hoy encuentran estas palabras desconcertantes, no sería sorprendente, pues carecen de sentido católico. No pueden explicarse al margen de su contexto histórico, que a continuación describiremos brevemente.

La ambigua referencia a «los griegos» apunta a la presencia de miembros de la Iglesia Ortodoxa Griega residentes en territorios pertenecientes a Venecia en el siglo XVI, quienes creían que el vínculo matrimonial se disuelve por adulterio, asumiendo que no existe impedimento para un nuevo matrimonio.

En 1947, el jesuita flamenco Piet Fransen escribió una tesis en la Universidad Gregoriana titulada «Sobre la indisolubilidad del matrimonio cristiano en caso de adulterio: Sobre el canon 7, sesión 24 del Concilio de Trento (julio-noviembre de 1563)». En ella, sostenía falsamente que Roma ignoraba las prácticas griegas de divorcio con fines diplomáticos, dejando abierta la posibilidad de un futuro nuevo matrimonio católico tras el divorcio.

El punto central de la tesis de Franzen era que Trento no pretendía definir la indisolubilidad del matrimonio como una verdad inmutable de la fe, sino que estaba dispuesto a flexibilizar las reglas en ciertos casos. La tesis se publicó en una serie de ensayos en la década de 1950,2 e influyó enormemente en teólogos progresistas, en particular los padres Karl Lehman, Walter Kasper y Joseph Ratzinger, quienes vieron su potencial para el "ecumenismo" con las comunidades "ortodoxa" y protestante.

Uno nunca deja de maravillarse ante el ingenio con el que quienes intentan cambiar la fe y la moral católicas encuentran material para intentar justificar sus posturas, pero lo cierto es que cuando los líderes de la Iglesia adoptan ideas contrarias a la enseñanza católica de fide —en este caso, las mismas palabras de Nuestro Señor en el Evangelio—, los fieles comunes que han mantenido la fe consideran sus esfuerzos una farsa.

La relevancia de esta pequeña digresión respecto al rechazo de Frings al esquema original sobre el matrimonio reside en su conexión con Ratzinger, quien, en tiempos del Concilio, estaba decidido a poner en práctica lo aprendido durante sus años de estudiante con su profesor de Teología Moral, el padre Richard Egenter. Como vimos en la Parte 137, Egenter era uno de esos teólogos liberales que mostraban poco respeto por el concepto de moralidad basado en la ley natural, enseñado en los Manuales Escolásticos. Esto explica por qué Ratzinger se dejó influenciar tan fácilmente por la tesis del padre Piet Fransen, mencionada anteriormente, y no dudó en aconsejar al cardenal Frings que se opusiera al esquema original sobre el matrimonio.

La relevancia de esta pequeña digresión respecto al rechazo de Frings al esquema original sobre el matrimonio reside en su conexión con Ratzinger, quien, en tiempos del Concilio, estaba decidido a poner en práctica lo aprendido durante sus años de estudiante con su profesor de Teología Moral, el padre Richard Egenter. Como vimos en la Parte 137, Egenter era uno de esos teólogos liberales que mostraban poco respeto por el concepto de moralidad basado en la ley natural, enseñado en los Manuales Escolásticos. Esto explica por qué Ratzinger se dejó influenciar tan fácilmente por la tesis del padre Piet Fransen, mencionada anteriormente, y no dudó en aconsejar al cardenal Frings que se opusiera al esquema original sobre el matrimonio.

La adhesión de Ratzinger a la tesis de Fransen quedó clara en un ensayo de 1972 en el que afirmó: «Lo que aquí afirmamos se ajusta sustancialmente a su investigación», 3 es decir, que el Canon 7 de Trento no pretendía definir la indisolubilidad del matrimonio como una verdad de fe válida para todo tiempo y lugar. La idea central del ensayo de Ratzinger era que los católicos divorciados y vueltos a casar debían ser admitidos a los sacramentos. Sin embargo, aquí se apartó de la interpretación que la Iglesia hacía de dicho Canon, entendido a la luz de la Introducción al Decreto de Trento sobre el Matrimonio, que había declarado dogmáticamente la indisolubilidad como ley inmutable y universal.

Esta pequeña digresión explica la intervención del cardenal Frings en el Vaticano II. Pero la cuestión volvió a surgir cuando el ensayo de Ratzinger se volvió a publicar en 2014 como parte de las Obras completas del Papa Benedicto. Su versión revisada omitió cualquier mención de la Comunión para los católicos divorciados que vivían en un segundo matrimonio, pero mantuvo intacta la tesis original de Franzen: que Trento supuestamente dejó una laguna en la ley de indisolubilidad del matrimonio. Así pues, Benedicto XVI recomendó que la Iglesia ampliara el proceso de anulación (ya descontrolado), alegando la "inmadurez psicológica" de las partes que consintieron al momento de su primer matrimonio, como pretexto para permitirles firmar un nuevo contrato con otra persona. No se trató tanto de una retractación por parte de Benedicto XVI de su error anterior como de un subterfugio para lograr el mismo objetivo que había planeado en el Vaticano II por otros medios.

Éste, dicho sea de paso, fue el tema de la propuesta de Walter Kasper que fue retomada por el Papa Francisco en Amoris laetitia. Sin embargo, Benedicto XVI siempre afirmó que nunca refutó la indisolubilidad del matrimonio en principio. Pero esto no basta para exculparlo, pues, en la praxis, introdujo una propuesta de cambio revolucionario en la llamada práctica pastoral de la Iglesia que, en ciertas circunstancias, equivaldría a aceptar el divorcio de facto y a condonar el adulterio.

Como en un juego de muñecas rusas, si levantamos a Frings, descubrimos a Ratzinger, y si levantamos a Ratzinger, encontramos a Fransen. Y bajo Fransen se escondía una caja de Pandora que daría lugar no solo a un abuso de poder por parte de quienes estaban encargados de velar por la pureza de la fe, sino también a una falta de autoridad moral por su parte.

Contra el Esquema sobre la Santísima Virgen María

En el Vaticano II, Ratzinger se opuso a la idea de tener un esquema separado dedicado a la Santísima Virgen María, propuesta por cientos de obispos en el Concilio como muestra de la debida reverencia y honor a la Madre de Dios. Las siguientes declaraciones de Ratzinger hablan por sí solas. La primera proviene de una carta que Ratzinger escribió al cardenal Frings en 1962 durante la fase preparatoria del Concilio, y es citada por su biógrafo, Peter Seewald:

"Creo que este esquema mariano debería ser abandonado, en aras del objetivo del Concilio. Si se supone que el Concilio en su conjunto debe ser un suave incitamentum [un estímulo fácil] para los hermanos separados y ad quaerendum unitatem [para lograr la unidad], entonces debe requerir una cierta cantidad de cuidado pastoral...

"Creo que este esquema mariano debería ser abandonado, en aras del objetivo del Concilio. Si se supone que el Concilio en su conjunto debe ser un suave incitamentum [un estímulo fácil] para los hermanos separados y ad quaerendum unitatem [para lograr la unidad], entonces debe requerir una cierta cantidad de cuidado pastoral...

“No se dará a los católicos ninguna nueva riqueza que no tuvieran ya. Pero se creará un nuevo obstáculo para los forasteros (especialmente los ortodoxos). Al adoptar tal esquema, el Consejo pondría en peligro todos sus efectos. Yo recomendaría la renuncia total a este caput doctrinal (los romanos simplemente deben hacer ese sacrificio) y en su lugar simplemente poner una simple oración por la unidad a la Madre de Dios al final del esquema de Eclesiología [sobre la Constitución de la Iglesia]. Esto debería realizarse sin términos no dogmatizados como mediatriz, etc.” 4

Pero esto fue demasiado para el cardenal Frings, quien no se atrevió a votar a favor de la propuesta de Ratzinger. Tampoco tuvo el coraje de votar en contra. El biógrafo de Ratzinger, Peter Seewald, asegura que «la papeleta de votación de Frings se encuentra sin usar en los archivos». 5

La carta es una prueba clara de que un aspecto clave del catolicismo, la veneración a la Virgen María, con un largo linaje desde la Iglesia primitiva y la época de los Padres de la Iglesia, debía ser minimizado para conciliar a los «forasteros». Ratzinger intentó posteriormente justificar este desarrollo anticatólico presentándolo como parte de una búsqueda de la “unidad” entre los cristianos basada en la Escritura y no en la Tradición:

“Fue sin duda una decisión explícitamente ecuménica cuando el Concilio decidió, en el otoño de 1964, incorporar el esquema sobre María como un capítulo del esquema sobre la Iglesia… En el texto, que sustituyó a un borrador anterior, la antigua mariología sistemática fue suplantada en gran medida (aunque no completamente) por una mariología positiva y escrituraria. La especulación fue sustituida por la indagación sobre los acontecimientos de la historia de la salvación, que se han interpretado a la luz de la fe. La idea de María como ‘corredentora’ ha desaparecido, al igual que la idea de María como ‘mediadora de todas las gracias’.” 6

Ratzinger parecía pensar que el rechazo del alto grado de honor tradicionalmente otorgado a Nuestra Señora era un precio pequeño comparado con los inefables deleites del "ecumenismo", con su interminable "diálogo", "caminar juntos" y esfuerzos conjuntos para "construir un mundo mejor". Denominó a esta nueva mariología "eclesiocéntrica" porque situaba a Nuestra Señora dentro de un esquema general sobre la Iglesia como parte del "Pueblo de Dios". El mensaje obvio que se extraía de esta "democratización" era que la Santísima Virgen María ya no era venerada de forma plenamente católica, es decir, debido a sus singulares privilegios y prerrogativas.

Solo más tarde, Ratzinger comenzó a percibir los efectos negativos de la nueva mariología. En 1980, comentó en la versión alemana de un libro que coescribió con Hans Urs von Balthasar:

"El resultado inmediato de la victoria de la mariología eclesiocéntrica fue el colapso total de la mariología". 7

Ratzinger parecía pensar que el rechazo del alto grado de honor tradicionalmente otorgado a Nuestra Señora era un precio pequeño comparado con los inefables deleites del "ecumenismo", con su interminable "diálogo", "caminar juntos" y esfuerzos conjuntos para "construir un mundo mejor". Denominó a esta nueva mariología "eclesiocéntrica" porque situaba a Nuestra Señora dentro de un esquema general sobre la Iglesia como parte del "Pueblo de Dios". El mensaje obvio que se extraía de esta "democratización" era que la Santísima Virgen María ya no era venerada de forma plenamente católica, es decir, debido a sus singulares privilegios y prerrogativas.

Solo más tarde, Ratzinger comenzó a percibir los efectos negativos de la nueva mariología. En 1980, comentó en la versión alemana de un libro que coescribió con Hans Urs von Balthasar:

"El resultado inmediato de la victoria de la mariología eclesiocéntrica fue el colapso total de la mariología". 7

Sin embargo, no expresó arrepentimiento ni sentido de responsabilidad personal, sino que culpó a la mayoría de los Padres Conciliares por haber "malinterpretado" el nuevo enfoque; lo consideraban "ajeno", dijo, porque estaban inmersos en la piedad mariana tradicional. Esta fue una admisión clara de que él, junto con sus colegas progresistas, había emprendido un golpe revolucionario en el pensamiento católico en aras del “ecumenismo” y la adaptación al mundo moderno.

Pero ¿qué pasa con los fieles católicos tradicionales que nunca habían pedido reformas ni fueron consultados sobre ellas, pero que sin embargo se las han echado en cara –literalmente en el caso de la Nueva Misa ad populum? Es evidente que lo que Frings y Ratzinger habían previsto no era para su beneficio en absoluto, sino para los "forasteros" que ni siquiera estaban interesados en entrar.

Continuará .....

Transpuesto a términos sencillos, inteligibles para el hombre moderno y hedonista, era como si Ratzinger-Frings hubiera dicho:

El cardenal Frings colaboró con Ratzinger contra el matrimonio.

El siguiente comentario de Frings —influenciado, como veremos más adelante, por las reflexiones teológicas de Ratzinger— es sumamente revelador porque explica la verdadera razón por la que los Casti connubii supusieron una vergüenza para los reformadores:

En materia matrimonial («ubi de matrimonio agitur»), no se debe juzgar ni condenar («non judicando et damnando»), sino ofrecer el consuelo de la fe cristiana mostrando respeto por la tradición oriental, como hizo el Concilio de Trento, que suavizó su canon 7 sobre el matrimonio para evitar ofender a los griegos («ne Graeci offendantur»). 1 (Énfasis añadido)

Si los católicos tradicionales de hoy encuentran estas palabras desconcertantes, no sería sorprendente, pues carecen de sentido católico. No pueden explicarse al margen de su contexto histórico, que a continuación describiremos brevemente.

La ambigua referencia a «los griegos» apunta a la presencia de miembros de la Iglesia Ortodoxa Griega residentes en territorios pertenecientes a Venecia en el siglo XVI, quienes creían que el vínculo matrimonial se disuelve por adulterio, asumiendo que no existe impedimento para un nuevo matrimonio.

En 1947, el jesuita flamenco Piet Fransen escribió una tesis en la Universidad Gregoriana titulada «Sobre la indisolubilidad del matrimonio cristiano en caso de adulterio: Sobre el canon 7, sesión 24 del Concilio de Trento (julio-noviembre de 1563)». En ella, sostenía falsamente que Roma ignoraba las prácticas griegas de divorcio con fines diplomáticos, dejando abierta la posibilidad de un futuro nuevo matrimonio católico tras el divorcio.

El punto central de la tesis de Franzen era que Trento no pretendía definir la indisolubilidad del matrimonio como una verdad inmutable de la fe, sino que estaba dispuesto a flexibilizar las reglas en ciertos casos. La tesis se publicó en una serie de ensayos en la década de 1950,2 e influyó enormemente en teólogos progresistas, en particular los padres Karl Lehman, Walter Kasper y Joseph Ratzinger, quienes vieron su potencial para el "ecumenismo" con las comunidades "ortodoxa" y protestante.

Uno nunca deja de maravillarse ante el ingenio con el que quienes intentan cambiar la fe y la moral católicas encuentran material para intentar justificar sus posturas, pero lo cierto es que cuando los líderes de la Iglesia adoptan ideas contrarias a la enseñanza católica de fide —en este caso, las mismas palabras de Nuestro Señor en el Evangelio—, los fieles comunes que han mantenido la fe consideran sus esfuerzos una farsa.

Se utilizaron malentendidos deliberados del Concilio de Trento para atacar el matrimonio.

La adhesión de Ratzinger a la tesis de Fransen quedó clara en un ensayo de 1972 en el que afirmó: «Lo que aquí afirmamos se ajusta sustancialmente a su investigación», 3 es decir, que el Canon 7 de Trento no pretendía definir la indisolubilidad del matrimonio como una verdad de fe válida para todo tiempo y lugar. La idea central del ensayo de Ratzinger era que los católicos divorciados y vueltos a casar debían ser admitidos a los sacramentos. Sin embargo, aquí se apartó de la interpretación que la Iglesia hacía de dicho Canon, entendido a la luz de la Introducción al Decreto de Trento sobre el Matrimonio, que había declarado dogmáticamente la indisolubilidad como ley inmutable y universal.

Esta pequeña digresión explica la intervención del cardenal Frings en el Vaticano II. Pero la cuestión volvió a surgir cuando el ensayo de Ratzinger se volvió a publicar en 2014 como parte de las Obras completas del Papa Benedicto. Su versión revisada omitió cualquier mención de la Comunión para los católicos divorciados que vivían en un segundo matrimonio, pero mantuvo intacta la tesis original de Franzen: que Trento supuestamente dejó una laguna en la ley de indisolubilidad del matrimonio. Así pues, Benedicto XVI recomendó que la Iglesia ampliara el proceso de anulación (ya descontrolado), alegando la "inmadurez psicológica" de las partes que consintieron al momento de su primer matrimonio, como pretexto para permitirles firmar un nuevo contrato con otra persona. No se trató tanto de una retractación por parte de Benedicto XVI de su error anterior como de un subterfugio para lograr el mismo objetivo que había planeado en el Vaticano II por otros medios.

Éste, dicho sea de paso, fue el tema de la propuesta de Walter Kasper que fue retomada por el Papa Francisco en Amoris laetitia. Sin embargo, Benedicto XVI siempre afirmó que nunca refutó la indisolubilidad del matrimonio en principio. Pero esto no basta para exculparlo, pues, en la praxis, introdujo una propuesta de cambio revolucionario en la llamada práctica pastoral de la Iglesia que, en ciertas circunstancias, equivaldría a aceptar el divorcio de facto y a condonar el adulterio.

Como en un juego de muñecas rusas, si levantamos a Frings, descubrimos a Ratzinger, y si levantamos a Ratzinger, encontramos a Fransen. Y bajo Fransen se escondía una caja de Pandora que daría lugar no solo a un abuso de poder por parte de quienes estaban encargados de velar por la pureza de la fe, sino también a una falta de autoridad moral por su parte.

Contra el Esquema sobre la Santísima Virgen María

En el Vaticano II, Ratzinger se opuso a la idea de tener un esquema separado dedicado a la Santísima Virgen María, propuesta por cientos de obispos en el Concilio como muestra de la debida reverencia y honor a la Madre de Dios. Las siguientes declaraciones de Ratzinger hablan por sí solas. La primera proviene de una carta que Ratzinger escribió al cardenal Frings en 1962 durante la fase preparatoria del Concilio, y es citada por su biógrafo, Peter Seewald:

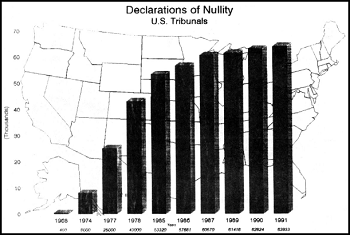

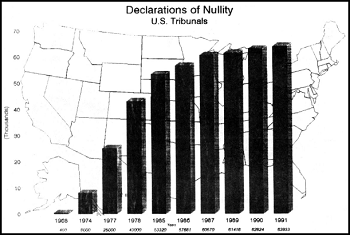

Las anulaciones se dispararon en las décadas permisivas posteriores al Vaticano II

“No se dará a los católicos ninguna nueva riqueza que no tuvieran ya. Pero se creará un nuevo obstáculo para los forasteros (especialmente los ortodoxos). Al adoptar tal esquema, el Consejo pondría en peligro todos sus efectos. Yo recomendaría la renuncia total a este caput doctrinal (los romanos simplemente deben hacer ese sacrificio) y en su lugar simplemente poner una simple oración por la unidad a la Madre de Dios al final del esquema de Eclesiología [sobre la Constitución de la Iglesia]. Esto debería realizarse sin términos no dogmatizados como mediatriz, etc.” 4

Pero esto fue demasiado para el cardenal Frings, quien no se atrevió a votar a favor de la propuesta de Ratzinger. Tampoco tuvo el coraje de votar en contra. El biógrafo de Ratzinger, Peter Seewald, asegura que «la papeleta de votación de Frings se encuentra sin usar en los archivos». 5

La carta es una prueba clara de que un aspecto clave del catolicismo, la veneración a la Virgen María, con un largo linaje desde la Iglesia primitiva y la época de los Padres de la Iglesia, debía ser minimizado para conciliar a los «forasteros». Ratzinger intentó posteriormente justificar este desarrollo anticatólico presentándolo como parte de una búsqueda de la “unidad” entre los cristianos basada en la Escritura y no en la Tradición:

“Fue sin duda una decisión explícitamente ecuménica cuando el Concilio decidió, en el otoño de 1964, incorporar el esquema sobre María como un capítulo del esquema sobre la Iglesia… En el texto, que sustituyó a un borrador anterior, la antigua mariología sistemática fue suplantada en gran medida (aunque no completamente) por una mariología positiva y escrituraria. La especulación fue sustituida por la indagación sobre los acontecimientos de la historia de la salvación, que se han interpretado a la luz de la fe. La idea de María como ‘corredentora’ ha desaparecido, al igual que la idea de María como ‘mediadora de todas las gracias’.” 6

A pesar de todos los esfuerzos progresistas, los cismáticos siempre odian a la Iglesia Católica.

Sin embargo, no expresó arrepentimiento ni sentido de responsabilidad personal, sino que culpó a la mayoría de los Padres Conciliares por haber "malinterpretado" el nuevo enfoque; lo consideraban "ajeno", dijo, porque estaban inmersos en la piedad mariana tradicional. Esta fue una admisión clara de que él, junto con sus colegas progresistas, había emprendido un golpe revolucionario en el pensamiento católico en aras del “ecumenismo” y la adaptación al mundo moderno.

Pero ¿qué pasa con los fieles católicos tradicionales que nunca habían pedido reformas ni fueron consultados sobre ellas, pero que sin embargo se las han echado en cara –literalmente en el caso de la Nueva Misa ad populum? Es evidente que lo que Frings y Ratzinger habían previsto no era para su beneficio en absoluto, sino para los "forasteros" que ni siquiera estaban interesados en entrar.

Continuará .....

- Frings/Ratzinger, Acta Synodalia Sacrosancti Concilii Oecumenici Vaticani II: Apéndice prima, septiembre de 1962, pág. 76.

- Fransen resumió las conclusiones de estos ensayos en un ensayo inglés de amplia difusión, “Divorcio por causa de adulterio: El Concilio de la Tienda (1563)”. Se publicó en una edición especial de la revista Concilium: Teología en la Era de la Renovación, vol. 55, titulada El futuro del matrimonio como institución, ed. Franz Böckle, Nueva York: Herder and Herder, 1970, pp. 89-100.

- J. Ratzinger, ‘Zur Frage nach der Unauflöslichkeit der Ehe: Bemerkungen zum dogmengeschichtlichen Befund und zu seiner gegenwärtigen Bedeutung’ (Sobre la cuestión de la indisolubilidad del matrimonio: comentarios sobre los hallazgos histórico-dogmáticos y su importancia para nuestros tiempos), en Franz Henrich y Volker Eid (eds), Ehe und Ehescheidung: Diskussion Unter Christen (Matrimonio y divorcio: debate entre cristianos), Munich: Kösel, 1972, p. 47.

- Peter Seewald, Benedicto XVI: Una vida, volumen uno: La juventud en la Alemania nazi hasta el Concilio Vaticano II, 1927–1965, trad. Dinah Livingstone, Londres: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020, p. 379 (publicado originalmente como Benedicto XVI. Una Vida, Múnich: Droemer, 2020). Ibíd. Seewald asegura que «la papeleta de votación de Frings se encuentra sin usar en los archivos». J. Ratzinger, Puntos Teológicos Destacados del Vaticano II, Nueva York: Paulist Press, 1966, pág. 93. Joseph Ratzinger y Hans Urs von Balthasar, Maria - Kirche im Ursprung, Friburgo: Herder, 1980; versión en inglés: María: La Iglesia en la Fuente, trad. Adrian Walker, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2005, pág. 24.

Publicado el 8 de abril de 2025

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |